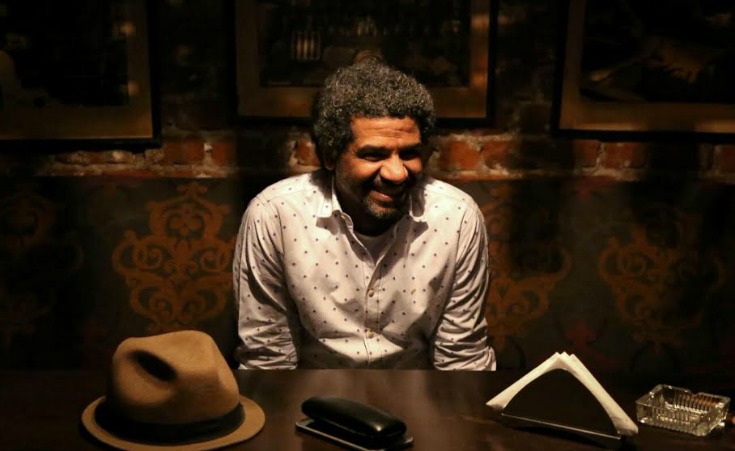

Navigating Identity Through Folkloric Music: A Chat With Musician Basheer

We make our way over to Downtown watering hole After Eight, where folkloric musician Basheer opens our eyes (and ears) to the depth to which music intimately affects our identities, not just our tastes.

How many times have we stared outside an office or apartment window and sighed, gesturing a need not just for vacation but a change of lifestyle? How many times did we long for living in a time and place where things were simpler and more in tune with ‘real’ life instead of a rushed cycle of colourless days? Though we can get that from all forms of written literature, like novels and books, the same applies to music, which is a medium that transports us to a place and time that sometimes doesn’t even exist. And so the question becomes, how many times did we close our eyes to certain tunes that carried us on an ethereal floor to a place that existed only in our heads, tainted by a strange nostalgia that never seemed to dissipate?

Mohammad Basheer of Basheer (band) is one such musician whose music carries our worn-out souls to a kinder world and fonder days, where life was all about love, music, and the sea, or so to say: to a rural Egypt. Basheer, who weaves Upper Egyptian lyrics and folkloric messages and tunes into modern music that is already perfectly merged with traditional Arabic music instruments, opens our ears to a new soothing world. The breezy desert drowning in silver moon light, the feeling of burying your feet in cold sand as you walk, and the little long boats sailing unassumingly on the Nile are only some of the images our mind conjures when listening to Basheer’s songs.

Sitting at After Eight with the folkloric Upper Egyptian musician just ahead of one of his performances, we chat about the many ways in which folkloric mixture affects the Egypt's musical scene and the musical tastes of diverse Egyptians, as well as perspective on the culture and its traditions in general.

“I like working with the kind of music I was raised with,” Basheer starts, “you know, Upper Egyptian and Egyptian folklore in general, while trying to make for a new musical experience regarding folkloric music with the help of the other band members that now make up Basheer.”

He explains that some of the songs have folkloric tunes and lyrics, “so what we would do in such a case is work on the music composition as we wouldn’t want to present folkloric music in its original form. Some other songs we only have lyrics for, to which we compose music.”

Upon inquiring about the importance of incorporating folkloric themes in music and reviving the musical traditional, he tells me that “our major problem really is that we are constantly moving away from our identity in the contexts of music, words, and thoughts, where we’re constantly trying to be who we aren’t and this in itself is a massive crisis.”

Basheer explains that Egyptians have their own music; “in Nubia, for instance, they have their own music that they create by themselves, just like they do in Upper Egypt. Each people have their own music that reflects their traditions and mentalities, such as kaff and nameem styles. What this essentially means is that they are never dependent on anyone else for music inspiration or composure in which they infuse their own private culture.”

However, Basheer acknowledges that not everyone will be fond of and interact with this kind of music. “At the end, music, like all forms of art, really depends on people’s tastes,” he tells me. “We try to make music that hits home with all the social classes who are eventually able to relate to and interact with it through elements of their culture, even if they weren’t aware of, it since it runs in their blood,” he says, gesturing toward the bloodstream in his arm.

Bahseer expands on that, saying that different groups in Egyptian society listen to different kinds of music, where there are Hip-hop lovers, metalheads, and those who listen to s3eedi or Upper Egyptian tunes. “But if you take South [of Egypt] for instance, you will find that they have their distinct kind of music that might sound novel at first but that you get used to in time because your main interaction will be with music, which is a universal act,” he says.

The folklore-loyal musician explains that he loves singing with the southern dialect (which might be seen as an impediment to music by some) because it’s his dialect. “which I always like to incorporate in my songs.”

Basheer, an Arabic literature graduate, has always held a great passion for all things folklore, which is what fuelled his decision 10 years ago to contact his musician friends and make a band comprised of all their musical interests. He, however, does not limit his interest to music, and tells me he’s also interested and involved in the theater scene through singing and acting.

The musician agrees that there has been a great change in the musical scene in Egypt ever since 2011. “Many bands came up that are closely associated with the revolution, and so the kind of music created by Egyptians has drastically changed as you can see in the songs of bands like Cairokee, Sharmoofers, and Massar Egbari.”

"We sing the music that we love; the one that looks like us and brings to our senses the real feel of authentic Egyptian music. This is our identity; who we are,” he concludes. The musician’s words make us think about the deeply ingrained effect of the music we surround ourselves with, which in itself is not only a true reflection of the way we interact with each other and the world, but a very powerful one too, that must inspire change and revival of ourselves and identities.

You can find out more about After Eight on their Facebook page here or follow them on Instagram @after8cairo.

Photo shoot by @MO4Network's #MO4Productions.

Photography by Youssef Emad El Din.