Palace Walk: A Sad Realisation

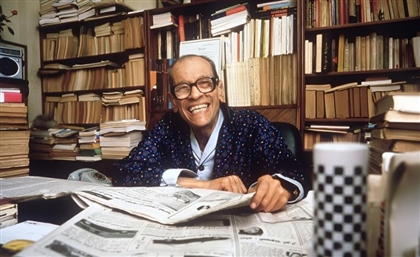

Though it was first published in 1956, Naguib Mahfouz's Palace Walk still rings truth in today's Egypt as our bookworm, Anam Sufi, recently found out...

When CairoScene posted my last book review on Facebook, I received a comment from someone asking whether anyone was still into the “classics”. I did inquire as to what that person meant when saying “classics”, but it seemed they weren’t bothered to indulge in an explanation.

So here’s my attempt to blindly cater to the whims and wants of my extensive followers and fans that consist of five people. I thought I’d hit two birds with one stone in that I’d also localise the literary arena by reading the first part of Naguib Mahfouz’s The Cairo Trilogy: Palace Walk.

At 498 pages, it is a hefty read… but don’t be put off, as it will certainly not disappoint.

Naguib Mahfouz is a Nobel laureate whose works are driven by the theme of existentialism. This theme is often culminated in the context of politics within his country of origin, Egypt, and his subject matters also tend to shed light on not only the historical account of Egyptian politics, but also the social implications that have been manipulated as a result of it.

Palace Walk serves as a prime example of Mahfouz’s satire against the politics of home and of governance in Egypt. The novel begins with the image of a woman named Amina as she waits for her husband (Ahmed Abd al-Jawad) to return from a night of philandering so that she can wash his feet and cater to his smooth transition into sleep. She is the epitome of suppression, but is unique in that she is convinced that her suppression is justified. As such, the reader is slowly introduced to all the members of the Abd al-Jawad family, Amina, Ahmed, and their five children.

Set in the 1910s, Mahfouz uses the family as a mirror of the political context in which the story takes place. The tyrannical British rule of Egypt is reflected in the heavy handedness of Ahmed Abd al Jawad towards his family. This is a man who the reader comes to hate as they deconstruct the striated layers of hypocrisy that comprise his character. Under the banner of Islam and virtue, he denies his wife and children even the most basic leisures… while he himself gets drunk and visits prostitutes on a nightly basis.

What separates good literature from great literature is when a book is able to pack multiple stories, themes, and motifs within itself. Each character demonstrates a different struggle that Egypt faces in actuality. While Amina and her two daughters symbolise the subjugation of women, the three sons, of varying ages, present the struggles that take place on a psychological, emotional, and even sexual level.

Mahfouz’s craft in constructing each of the characters in the text is what keeps the reader in a constant blend of emotional highs and lows as s/he gains insight into the dynamics of the household. What I loved most about the characters was that none of them emerges as being entirely sympathetic. Even Amina, who in the simplest terms is a battered wife, rarely emerges from her obsequious character. I’m not a hardcore feminist, but lets be honest, you want to slap Amina and shake her for being such a doormat.

Having said this, Mahfouz utilises her servility to construct a climactic moment of revolt within the family that parallels the revolutionary hunger that at the same time is gripping the nation…(don’t worry I haven’t ruined anything by sharing this) and this is the art of Mahfouz at his finest.

Although the book was first published over half a century ago, the similarities between the Cairo that is presented then and the Cairo that we live in today are impeccably saddening. Mahfouz almost emerges as being clairvoyant in his precision in marking the problems that unfortunately still plague Egypt in the 21st century.

I’ve rambled on for quite a while, and I guess if I have to put it in bold letters I’ll do so too: PALACE WALK IS A MUST READ. So get on it.

Fun Fact: The characters of Amina and Syed Abd Al-Jawad were so influential in terms of defining individuals who are obsequious and hypocritical (respectively), that their names have become phrasal adjectives for such people. In fact, in many Egyptian households, mothers looking to have their daughters married often ask whether a potential suitor is a “Sir Syed” type fellow, so to avoid a disaster if he is.

- Previous Article I Got Banged!

- Next Article Alaa & Gamal Mubarak Set Free?