San El Hagar: Egypt's Forgotten Capital

[EXCLUSIVE] We head to Egypt's abandoned 21st dynasty capital San El Hagar as it slowly rises from the ashes.

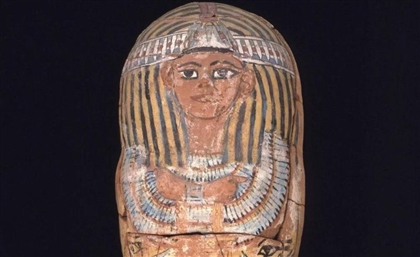

Imagine a small city in Sharqiya: tiny houses, stores tucked together, and an image akin to a village, rather than a city. San El Hagar is not a place you’d imagine had once been the decision-making center of the Egyptian state at one point in time. On one side of the road, a sign says “Welcome to San El Hagar.” Egypt’s capital from the 21st and to the 23rd dynasty, the little city is adorned with treasures that were long uncovered, but only a year ago, acknowledged.

A few thousand years ago, by the end of the 20th dynasty, Egypt was going through moments of frailty. At the time, San El Hagar was a graveyard known for the quality of its sand. With the 21st dynasty, the royals decided to move all of Ramses II’s relics to the city as a homage to him, and turned the cemetery to the capital of Egypt, or ‘Thebes of the North.’

The city was built to closely mimic Thebes and its temples, and the royals built themselves some royal tombs in the area, as well as temples. However, it didn’t attain half the attention Thebes did. Until 2017, only its residents knew its potential, which was hidden to tourists and overlooked by officials.

In 2017, the Ministry of Antiquities decided to rediscover San El Hagar, renovate it, and turn it into an open museum. Workers, engineers and renovators were sent in to re-erect the statues and obelisks and restore them to their former glory. Mahmoud Gamal, who was selected by Dr. Moustafa El Waziry, the secretary general of the General Authority of Antiquities to be the technical manager on site, moved from Luxor to overlook the process. He tells us: “This business runs in my family. We are 7 brothers and we all work in the same field and love it.”

Despite the hardships he faced to be in San El Hagar, like the long distance he had to travel from his hometown, Luxor, and the lack of transportation and services in the area, Gamal still finds it to be the best job he could ever have.

“The best thing about San El Hagar is the large number of obelisks and temples lying around on the ground. If it’s about the money, it doesn’t matter. My job doesn’t pay well, and I spend much of my own money on doing it. What matters is my sustenance and well-being, save for the pride I’d feel in 10 or 15 years when someone stands before an obelisk or a statue and praises whoever restored it.”

Seeing is believing. At the entrance of the site, you can see statues of Rameses II, and huge untouched obelisks that date back to millennia ago. The ground still maintains the humid sands that encouraged Ancient Egyptians to bury their dead at the time. The royal cemeteries are still in good shape and are accessible via small staircases. Inside the tombs, the walls are adorned with carvings and statues, and small inlets of sunlight. This architecture is said to be novel, even if ages old. The site still suffers from ecological problems like salt and humidity, but these problems are expecting solutions with the arrival of the antiquities fellowship.

It matters a lot when those tending to a site have lived in it and know its value on a firsthand, personal level. Dr. Metwally Salama, the inspector of antiquities at San El Hagar was born there. He’s passionate about history and its stories, and his most important job is to manage and preserve the site.

“The best and happiest thing is that we’ve started restoring the statues, because for the 20 years I’d worked in the field, I would always be sad because of how neglected these antiquities are. Finally, I’m starting to feel that we’re taking care of this heirloom that we’ve been entrusted with since these old times, and we’re hopeful as well about continuing in the future,” Salama says.

As a manager of the location, Salama sees many problems in the way of the San El Hagar museum. “The roads are terrible. There aren’t services, and there isn’t accommodation for tourists. Why would you bring tourists in if you can’t give them rest-stops or toilets? There is no healthcare or hospitals nearby.”

Erecting an obelisk or a statue is not a usual event, or at least it wasn't back then. Salama tells us that the king himself would oversee the crafting process, as well as attend its opening. Some stories say that the Pharaoh used to put his son on top of an obelisk as its being built so that engineers and workers would be especially meticulous and associate the value of the obelisk with the son of Pharaoh himself, and that people could die if they make a mistake. Maybe this story is exaggerated or irrational, but it does inform us of how important the event really is. Today, San El Hagar, is witnessing this for the second time, and the obelisks are rising once again.

Mohamed Gad Ahmed, a restoration expert in the Ministry of Antiquities and one of those working on the project tells us about his job: “In restoration, you make something out of nothing. You hold a rock that used to belong to a king, one he crafted before you and that is now in your own hands. It’s something else. This rock went through histories; the history of its making and the history of its destruction. The third history is the history of my work with it: It’s a piece built by a king, destroyed by a king, and revived by me.”

People -not specialists- deal with artifacts and antiquities in two ways: some prefer restoration and renewal, and others prefer preservation because it expresses the piece’s history and experience as an object. But a specialist could think otherwise.

“Restoration is contentious and is split up into schools. Some argue for completing a broken statue and others would rather keep it as it is. I’m with the school that you should only add to a statue within very strict limitations. If a statue is missing a head, I won’t make a new one, but if it’s missing a leg, I have to make one to carry it.”

Before we went to the place, none of us had heard of San El Hagar, not in history books, not in documentaries. It’s an unknown place full of antiquities and tombs surrounded by sand. To get there, you must take a broken road, and be hosted by one of the locals because there are no hotels. You must not get sick because there is no hospital. Wear a hat because there is no shade. Treasures thrown away in harsh conditions. But work on this site would bring all the rest with it, and soon everyone would hear about San El Hagar, Egypt’s old pharaonic capital.

Shoot by MO4Networ's MO4Productions

Original article by Ahmed Shiha from El Fasla

Translated by Omar Elkafrawy

Trending This Week

-

May 01, 2024