How the British Chief of Cairo Police Waged War on Egypt's 1920s Drug Epidemic

Sir Pasha gathered such extensive narcotic information that he ultimately teamed up with the DEA to fight the global war on drugs.

Today, in 2018, narcotic abuse is more or less rampant in Egypt, and it’s a problem that’s anything but new. Every other microbus driver is on tramadol, and hash is mostly caj, with Egypt being the Arab world’s highest consumer of hashish. But these drugs didn’t just pop out of nowhere; illicit substances only begun to be trafficked heavily to Egypt around the 1920s, and it’s fascinating to be able to get a first-hand account of the drug scene at the time from Thomas Wentworth Russell, AKA Sir Pasha, British Cairo Police Chief starting in 1917. Sir Pasha is the author of a book called “Egypt Service” written in 1946, and it’s a gem of a shadier aspect of Egyptian history.

Sir Pasha became a strict anti-drug campaigner when he realised that drugs like opium, heroin, cocaine and hashish were increasingly being smuggled into Egypt in massive (and exponential) quantities. He did everything in his power to curb the drug epidemic that was beginning to ravage the country under his very eyes. His efforts were in vain, however; the drug problem is still very much alive and well in the country today, with the drug war still raging.

Sir Pasha took over command of the Cairo Police in 1917, but until 1924, all he was really concerned about were assassinations and political riots, such as the infamous 2nd of April 1915 riot in Harat El Wasa, Cairo. During his years in the provinces, he hardly came across a drug problem at all, as it didn’t exist except in the slums of a few of the bigger towns like Tanta. The farmers were healthy and happy, and they didn’t need drugs to help them in the fields and to tend to their “duties to their womenfolk at home”.

Cocaine first touched down in Egypt around 1916, and the more serious heroin followed shortly after. At the time, as drugs still weren’t a major problem in Egypt, possession and even the trafficking of drugs was only punishable by an EGP 1 fine (which was quite the number back then), or a week’s imprisonment. It was pretty open at the time; the pioneer of the sale of heroin was a Cairo chemist, who had a line of horse carriages queued outside his pharmacy. Prices then, even for the time, were really low, with a shot of heroin going for as little as a few shillings (Malaleem).

For the sake of comparison, today, a gram of heroin from the source costs somewhere between EGP 120 and EGP 200, and although it’s hard to compare prices today with those of the 1920s, suffice it to say that an equivalent amount at the time would have been quite the detrimental expense.

Sir Pasha recalls the fashionable drug being handed over to the privileged, wealthy youth over the counter. And though heroin is much, much more dangerous than anything you can get over the counter today, it’s similar in the sense that you can still get some pretty strong drugs over the counter today.

The inspection of chemist shops was outside police jurisdiction back then, and the Public Health Authorities didn’t seem to be doing anything at all to stop the chemist. There were even times when contractors paid their workers in heroin, rather than good old guap.

It wasn’t until around 1925 that Sir Pasha realised how bad the drug craze had become; heroin had created an epidemic in Cairo. New slums, such as Bulaq (then Beau Lac du Caire), were increasingly becoming full of pale, twitching corpses lying about in the streets.

While Bulaq was previously home to the rough, Upper Egypt labourer type, it was now home to these junkies, who admitted that it was the heroin problem that got them there. Some were still strong enough to be labourers, but the rest just scavenged the rubbish bins outside the back doors of hotels and restaurants hoping to find what little food their frail bodies desired. They were from every class; working men, sons of small shopkeepers, cabmen (taxi drivers), artisans, clerks from government offices and even sons of people that did well for themselves, and their lives were all taken hostage by this devastating drug.

Mid-1925, a new narcotic law was enacted that made trafficking, as well as possession, punishable by a maximum penalty of one year in prison and an EGP 100 fine. Shit was, for all intents and purposes, starting to get serious. In the first 12 months after enacting the law, the police force made 5,600 prosecutions in Cairo alone.

In those days, heroin cost EGP 120 per kilo in the wholesale market in Cairo, and it only cost European factories EGP 10 to produce before selling it to dealers at the factory door for EGP17 per kilo. European pockets were getting fat with those incredible margins.

By the end of 1925, the price in Cairo had gone up to LE 300 per kilo and addiction was spreading all throughout Egypt.

A couple of months after enacting the first narcotic law, it was further improved, and the maximum penalties increased to five years in prison, and a EGP 1,000 fine (try adjusting that to today's inflation).

It was less than a year later that authorities became aware of the new drug on the block; opium, thus moving to make it illegal in 1926. The tricky thing with opium was that most farmers could easily get away with hiding it in the middle of their fields; it was practically impossible for the police to find it. As Sir Pasha realised that the opium business continued growing at a relatively rapid pace, he became determined to find a way to catch these cheeky, sneaky farmers.

As he knew that poppy plants in full flower, a thing of beauty, really stand out, he decided to gather the help of the Egyptian Army Air Force, who would spy above farms to find the plant, and in the next couple of hours the crop would be destroyed. As the farmers became accustomed with this, all the police needed to do was to get lower next to a crop of poppy flowers and hover around it, and the farmers would realise that they were caught, and would destroy the crops, effectively doing the police’s job for them. Hashish, on the other hand, didn't really alarm Sir Pacha. He mostly regarded it as an inoffensive habit, and according to his associate, Baron Harry d’Erlanger, even wanted to legalise it and turn it into a revenue-producing resource. We’re still waiting for that to happen a century later. As Russell and the British put pressure on Greek suppliers, Syrian and Lebanese suppliers took over, moving their product through Palestine to enter Egypt. The way Russell describes hash, though is nothing short of beautiful, and couldn’t be left out. “When we talk about hashish in Egypt, we mean the flat cake of compressed resinous powder, extracted from the flowering top (inflorescence) of the female hemp plant of the variety indica of the species cannabis sativa.” Wow.

Hashish, on the other hand, didn't really alarm Sir Pacha. He mostly regarded it as an inoffensive habit, and according to his associate, Baron Harry d’Erlanger, even wanted to legalise it and turn it into a revenue-producing resource. We’re still waiting for that to happen a century later. As Russell and the British put pressure on Greek suppliers, Syrian and Lebanese suppliers took over, moving their product through Palestine to enter Egypt. The way Russell describes hash, though is nothing short of beautiful, and couldn’t be left out. “When we talk about hashish in Egypt, we mean the flat cake of compressed resinous powder, extracted from the flowering top (inflorescence) of the female hemp plant of the variety indica of the species cannabis sativa.” Wow.

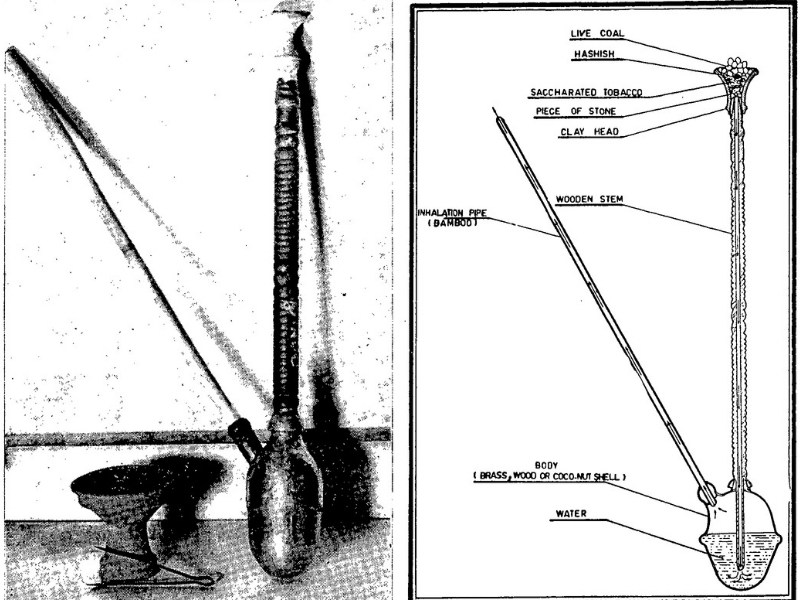

The josah - instrument to smoke hash at the time

Fast-forward to the end of the decade, then-Prime Minister Muhammad Mahmoud Pasha had become fully aware of the devastating effect drugs were having, not only in the cities, but also in every village of the country. According to Sir Pasha’s figures, out of a population of fourteen million, half a million were now slaves to heroin alone. That’s when the powerful Central Narcotics Intelligence Bureau was created, with him as Director, and the bureau having direct access to all Egyptian government departments and foreign public security authorities. In the following three years, they expelled 334 European traffickers.

As the heroin habit grew, and addicts were getting caught left and right, the dealers decided to increase their profits without having to make the price more expensive, so as to not to lose their loyal client base. Instead, they cut it, just like drug lords still do today.

There was one lady in the Khalifa District who was known to sell heroin to the quarrymen; as the police raided her houses, they found her hard at work pounding up some white substance, which to the surprise (and definitely disgust) of the police, turned out to be ground pieces of human skull. The inventive lady, who lived next to a cemetery, realised that out of all the bones in the human body, the skull, if treated finely, could be crushed into a powder fine enough to be mixed with the little heroin that she could afford to buy.

The drug epidemic was in full force – so much so that some addicts would walk into police stations and snitch on themselves, even handing over their heroin to the authorities, just in order to be sent to jail as they saw it as the only way to get clean.

That made Sir Pasha think of creating treatment centers for addicts outside of Cairo, but the government at the time couldn’t be persuaded to do so.

Another story that shows the lengths addicts went to in order to try get clean is the “mad dog hospital”. One day, a fellah had been bitten by a rabid dog, and after going through the anti-rabid treatment in Cairo, came back to his village to realise that his addiction to heroin was gone. Other villagers heard of this, and, of course, wanted to emulate him; they consulted the village barber who fitted up a dead dog’s jaw with a steel spring and gave the villagers fake bites that looked close enough to a rabid dog bite. Deceived by this clever trick, the local government doctor would then send them for anti-rabid treatment in Cairo, and after the painful treatment they’d come back home clean from addiction.

Sir Pasha and the newly-formed Central Narcotics Intelligence Bureau decided to, for the time being, ignore the local retail traffic and focus on the thousands of kilos that were coming in the country from Europe. Also, they decided that they would focus their efforts on what they perceived to be the more imminent danger; white drugs (heroin, cocaine).

With the employment of agents in Europe, The Central Narcotics Intelligence Bureau was making important international arrests left and right, one of them being a French factory that had sold in one year 4,350 kilos of heroin, two and half times the world’s legal limit. And that’s just one factory.

Following a meeting of the Advisory Committee of Geneva that Sir Pasha attended representing Egypt, with the goal being “to take part in the discussions concerning the traffic in narcotics in so far as they affect Egypt”, Swiss authorities tightened up their anti-narcotic laws and France made some rectifications as well.

Thanks to agents in foreign countries working for the Bureau, it was soon known that Istanbul was quickly replacing Central Europe as the centre of the drug traffic, and that it had become all the source of heroin in Egypt. It was the perfect place – it had some of the best opium in the world, wasn’t tied up in the international conventions of Geneva, and had a wide seaboard which made it easy for shipping.

Following an animated discussion at another later Advisory Committee in Geneva in 1931, where Turkey’s export of a whopping four tons of heroin a year was discussed, Sir Pasha met with president of Turkey Ismet Pasha in Turkey, who received him in a very friendly manner. Following that meeting, the fate of Istanbul as a centre of the illicit drug traffic was sealed; three big factories were closed, and new legislations against drug trafficking were introduced.

Ultimately, Sir Pasha pulled together a vast international network linking East with West; his agents exposed the opium fields guarded by narcotic warlords and tracked down companies in Western Europe that didn’t think twice to sell thousands of kilos to criminals, no questions asked.

Russell shared the vast information he had gathered with American Harry J.Anslinger, first director of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics, which is now known as the DEA, and together they pioneered the war on drugs across the globe.