Bahariya's Bedouins: Now and Then

Sina Stieding heads out to the Western Desert to discover the lifestyle of the modern Bedouin, which is still deeply rooted in ancient cultural norms. But in 2014, what has changed and what has remained the same?

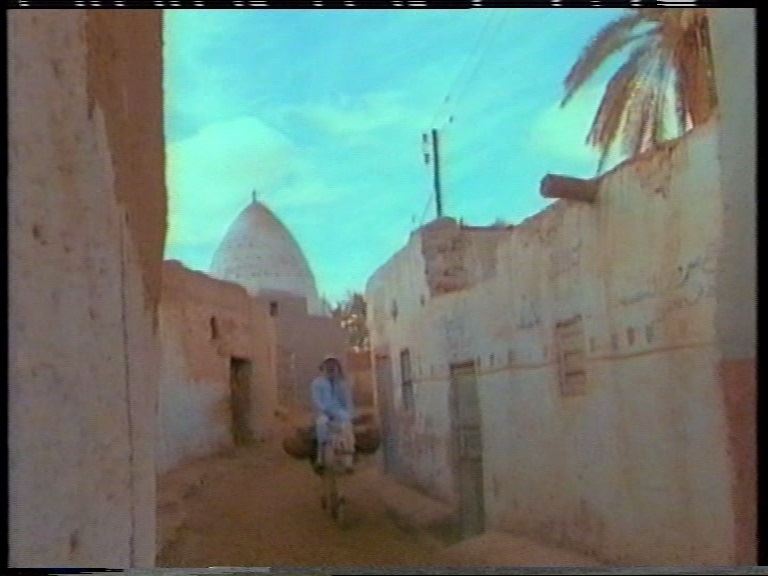

The Bahariya Oasis has been an address to escape from busy Cairo for many people. A weekend in the desert, surrounded by sand and stars, has attracted more and more vacationers, and new roads between the Bedouin village and Cairo have brought in a plethora of tourists looking to check out the carved sand stones. The arrival of city people simultaneously meant the arrival of new ideas in the Western Desert. On a recent trip to the Bahariya desert I met 31-year old Mohamed Safie Eldin, a Bedouin that ventures to the desert with foreign tourists on a weekly, sometimes daily, basis, accompanied by his best friend Ahmed Abd. This being my second visit to Bahariya in seven years I noticed the changes around the village. Mohamed keeps mentioning "the new way of life." Curious about the history of the Bedouin village I asked Mohamed to share his story. While sharing a Jeep he tells me how the Bedouin life has changed since roads connect it to Cairo, electricity stopped coming from generators and education broadened horizons.

The Bedouins of Bahariya are primarily farmers, however, they consider themselves their own breed. "People of the Western desert are different from people in the cities or other landscapes," Mohamed tells me. They inherit land and grow crops, mainly dates, and feed their families from the money made with their harvest. All parts of life are connected to traditions. While this reality hasn't changed much, many other things have. With the inception of the road to Cairo in 1970, the life of the Bedouins changed tremendously. Before the highway, El Nile Truck Company offered transportation services on an unpaved street which would take four days. Transportation around the village happened via camels. On top of that, full-time electricity has only been present in the village since 1987. Before, people lived off diesel-generated power that was only on from 6pm to 10pm. Evidently, modernity arrived in Bahariya late. "The old Bedouin way still carries a lot of prestige, even for younger generations" Mohamed informs me, however. "For the new generation, sometimes keeping old habits is considered to bring good karma."

Mohamed refers to customs, style and hierarchy that have changed in the last 40 years. However, remaining true to the "old generation" still fascinates many. Dressing in "Bedouin style" with a galabeya and a turban is still considered fashionable and a neverending trend, Mohamed explains. In this old generation, however, rules of gender equality have had no space. "Women were housewives, nothing more, nothing less," Mohamed says. Men were in control of their women, and women enjoying an education and watching TV, like their husbands, would have been unthinkable in earlier days. "Today, because of the media and education, girls are getting open-minded and harder to control," Mohamed says, adding that the key to success for modern marriages remains that husbands should to continue to prepare their wives for the reality that they have to be obedient. Working at the local school, Mohamed has experienced that girls and boys alike have yet to abandon their perception of the old gender rules. Girls merely attend to find themselves getting married and raising a family instead of venturing out after school. "Women here in Bahariya age fast because they get married at 18 and never enjoy being teenagers," Mohamed explains. According to Mohamed, girls choose that way voluntarily.

Additionally, all members of the family used to live in one giant house before the 90s. Sons would stay in their parents' homes with their families, working on their father's fields. Women stayed home, cooking and taking care of the children, and were not allowed to join their husbands in any activity. All women of the house had dinner in a separate room after all the men had finished, and children were not allowed to be interfering with the men either. Nowadays, these customs have loosened. It is no longer impolite for a man to pick up his children in front of their peers, and married couples usually move to their own place with their family's money to start their own businesses. However, as I entered a Bedouin household I was invited to, women remained in the kitchen, separated from the rest of the house by a curtain. Women's perception of gender roles are visibly still deeply rooted in the old Bedouin way.

In fact, such marriages used to only become reality after a young man, approximately 22-years old and ready for marriage, had expressed the wish to find a woman to his mother who then told her husband and initiated the search for a girl. None of this happened directly, as it was the family that needed to be chosen, not a girl. "Bedouins love white wives," Mohamed tells me, "because they are very dark-skinned themselves!" At a dinner set up by the families, the potential groom met the bride's family and got to lay eyes on her for the first time. He then decided if she is suitable. One citation of Al-Fatiha later, the girl becomes a fiancée. The soon-to-be-wed couple then meet again on their wedding day. In the old days, a Bedouin wedding would last up to seven days. Nowadays it takes three.

Many things have changed in Bahariya. Modernity is trying to find its way to the Western Desert but traditions are trying to close the door to changes. Of course, the presence of electricity, the internet and the connection to the city have had a lasting effect on the Bedouins of Bahariya. Mohamed an I communicate via Facebook and him and his friends come to Cairo often. The stigma attached to the "old Bedouin way," however, seems to be lingering on. The prestige that is linked to the older generations makes sure that liberal ideas are accepted, yet not applied in many instances. The Bedouins are proud of who they are and want to avoid losing their identity. As a result, progress happens slowly, but it's happening...

Thanks to Mohamed Safie Eldin for sharing the story and pictures.

- Previous Article Mobinil Golf Tournament: A Whole in One at JW Marriott

- Next Article Cairo's Fashion Nights Head to The First Mall