No Country for Young Men

In his CairoScene debut, Mouwafak Chourbagui tackles the social phenomenons affecting Egypt's youth, forcing them to indulge their private desires in the public sphere, as they wait for society to tell them it's OK to be themselves.

When the revolution first erupted, there was a huge invisible bowl floating in the air in which resided the dreams and hopes of the very first wave of young protesters. Unfortunately, nobody was there to amass and lay bare their combined aspirations and so they remained solitary, like atoms unable to moleculise, drifting silently in the outskirts of possibility, only finding a home in the midnight monologues of their hosts.

The revolution was then hijacked, reduced to a ping-pong ball, helplessly slapped back and forth in a game of appropriation by two fascist rackets. But before that bowl was smashed by the military, shat on by the Ikhwan and then finally condensed to a homeopathic sized vial, only big enough to contain the ambitions of the Hacienda crowd, there was a time when I had genuine optimism that a social revolution would accompany the political reshuffling. I thought that Egypt could only abuse the Koshari exception model* to an extent; that the revolution would force the country into collective introspection, in which outdated norms would be challenged by the disgruntled young voices that roared for freedom in the streets.

But I was wrong. Three years in and we find ourselves back to square one: decision making power remains in the same old grumpy hands and the youth (18-29), despite representing 1/4 of the total population, are once again relegated to the sidelines of their own destinies.

What I had thrown in the bowl is a dream for a social space for the youth to be carved out, one not dictated by religious dogma or obsolete traditions but designed by the new generation and taking into account the realities on the ground and the evolving demographical patterns that make Egypt’s current social model unsustainable.

With increased urbanisation, yearly rises of the average marrying age, and reduced annual purchasing power, social dynamics are about to implode and there needs to be a viable alternative model for the youth: a comprehensive social phase between the family home and married life.

The average Egyptian guy has to stop thinking that he has to save up for a whole family and begin to conceptualise an alternative reality where he has the right to be an individual…at least for a period. And the average Egyptian girl has to stop waiting around for a suitor and conceptualise an alternative reality where her road is paved with her own hands.

The young can only currently live freely as a devout person and/or as a consumer; the country is generous with its mosques, churches, shops and cafes, but their biology and self-growth are stifled in a period of unnecessary purgatorial angst, waiting for marriage to validate sex and money to enable marriage.

The problem is that society is designed to function for couples and families; the single person is shunned and shamed, an outcast unable to gain access to Cairo Jazz as Hans Solo, a pervert scrutinised when buying a condom without a wedding ring, a sinner when trying to book a hotel room with an Egyptian passport. The real estate market builds family homes, not studios, the bawab allows foreigners to cohabitate but no Egyptian to ejaculate, there is a KFC family meal but no “riding solo” combo at McDonald’s.

The consequences of uneventful and unfulfilled youths in static surroundings are easy to see but are hardly exposed, because they contradict so profoundly the principles its society has sworn to protect. Yet, the abundance of “3orfi marriages,” the drastic rise in prostitutionand an alarming drug use rate cannot be unrelated to the general social dysfunction, especially in terms of being compensatory byproducts of unsustainable youth relationships and dynamics.

With the private sphere under patriarchal command, it seems that the public sphere has, ironically, become the only viable option for privacy and the only space available for the manifestation of freedom.

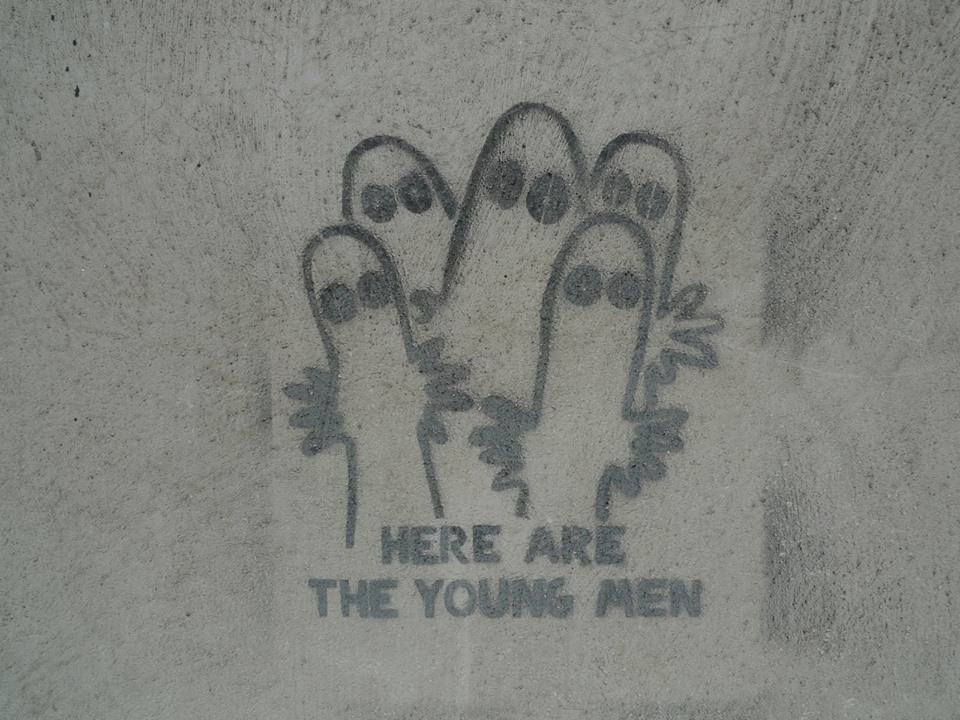

Young men can often be seen wandering the empty midnight streets in packs, laughing and wasted, relaxing their desires and numbing their senses, living their crushed youth dancing in zombie clouds and anesthetic parallel worlds, waiting in vain for something other than a puff puff pass to make them feel alive. Couples can also be seen making out and doing a bit more in the parked cars of Shara3 el 7ob and young, buff gentlemen are treating their ladies to a nice view on top of Mokattam’s hill.

Whereas the public space has somehow managed to accommodate certain youthful grievances, the private space (home itself) has developed a tendency to reduce the young into a virtual green dot looking outwards for release, companionship and acceptance in the online world, where sheikhs can only be found when looked for and where the government only looks for what it wants to be found.

Online relationships have blossomed trying to fill a certain intimacy void but they have mostly created a serious discrepancy between virtual and real relationships since there is no true substitute to contact and intimacy cannot be genuinely reached without proximity.

But the crisis is bigger than sex. The consequences of such unhealthy gender relations transcend the physical and have lead to a culture, in which affection, friendship and communication between the sexes have been muffled. It is as if, in the prevailing perverted mind, there is no logical reason for a man and a woman to be in the same room save for sex. As a result, the segregation of the sexes has made the bonds within each gender stronger, as people are somewhat forced to seek solace, comfort and emotional intimacy within their own sex.

Some evidence can be found in language, both spoken and body. Take the wonderfully tender word habibi; in can be interchanged between men without ambiguity, but hearing two Englishmen calling each other “love” or having Claude call his buddy Francois “mon cheri” will leave no doubt as to their sexual orientation. If it is acceptable in a society for heterosexual men to be holding hands and communicating in terms of endearment, then our ancestors have surely been spending too much time with their own gender.

It’s important to encourage and allow young people to move out on their own after a certain age and to build an economy and infrastructure that can support their emancipation. There should be a phase between the house we grew up in and the family we end up starting, a sort of small customised bowl for our individual growth, where we learn how to take care of ourselves and get in touch with our singularities and passions, a timeframe where we are not a son, a husband or a father, nor a daughter, a wife or a mother, but simply where we are who we are, even if just for a while.

*When incompatible factors combined somehow create a workable outcome. Like Koshari.

- Previous Article I Got Banged!

- Next Article Nomades Land