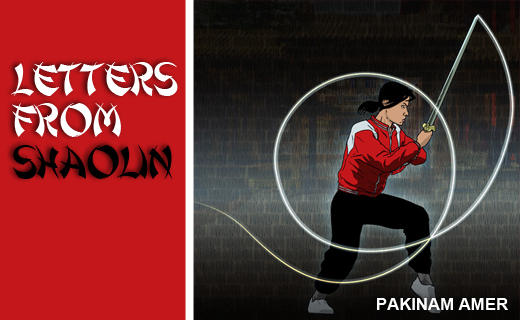

What it Takes to Be a Shaolin

Pakinam Amer admits that she sucks at Kung Fu but the end of her denial marks the true start of her new journey.

I chugged warm green tea out of my over-sized plastic bottle, seated in uniform among hundreds of other Shaolin Kung Fu students, enviously eyeing our school’s chosen performers; some young as 10 and others in their early twenties. Most had shaved their heads in preparation for the school’s tournament, a celebrated event that took place twice a year in Shaolin Si Xiaolong. The fighters donned proper Kung Fu attire with beautiful embroidery depicting colorful dragons and phoenixes (powerful Yin and Yang symbols among martial artists). The older ones were either shirtless despite the chill in the air or wore sleeveless tops that showed off their intricately designed arm and hand tattoos, as well as their ripped and toned muscles.

Instead of being psyched up, the competitive, electrifying atmosphere tensed and intimidated me, though I was far-flung from competing as could be. Being painfully aware that I’m a beginner, with little sports background, a late start into the martial arts, and no fitness conditioning in the past decade to save face, I felt the odds well-stacked against me to ever compete in this sport. What the hell am I doing here? I thought darkly. On the makeshift stage, a group of students ascended, greeted the line-up of seated Shifus – Kung Fu teachers and masters – who were acting as judges. They froze into a ready stance, and awaited their cue.

Warmth began to course through my veins, as I gulped the tea, the calming effect more emotional than physical. Despite my Shifu’s attempts to help me be mentally tough, the only “toughness” I exercised so far remained confined to the area of mental flogging. I’m always mad at myself, either for not taking care of my body in the past or for failing to immediately rise up to my peers’ level in the present. Harsh, I know, but uncontrollable for the most part. Then again, the kindest feedback I got for my Kung Fu thus far was “very cute.” My Chinese Shifu humorously said it while evaluating my form; I joked later on Twitter that “to those unfamiliar with Shaolin Kung Fu jargon, ‘very cute’ is right between ‘you’re a Kung Fu dork’ and ‘go home, Kung Fu is not for you.’”

But I survived.

On stage, the grinding began. Fists punching, legs twirling in the air, and bodies flipping elegantly. They make it look so easy. At that moment, a voice deep inside (Miss Compassion, I call it) whispered an afterthought, “You know better.” And I do. In essence, I wasn’t part of the enthralled audience that claps in awe at a magician’s illusory tricks, and wonders in amazement how it’s done – not anymore. I know what it takes to be excellent, like those kids.

I knew it as a journalist, carving her way up from complete anonymity and less than average skills to some solid published work and a good measure of reassuring recognition by peers and senior editors. I know it now as a Kung Fu student, negotiating the fundamentals, and snuggled in self-doubt at the bottom of the Shaolin food chain.

It takes a whole lot of pain, falling apart, tripping over again and again, strenuous hours of exercise, waking at the break of dawn, shutting yourself off from the world, beating yourself over the head for missing training or slacking off, braving the elements and sometimes extreme boredom, loneliness and lack of motivation to press on, dealing with body image issues and some baggage from the past. It takes trying to meditate and failing, then trying and succeeding, then trying and failing again. It takes knee-pain, back pain, sore muscles, twists and sprains, and lots and lots of frustration. It takes getting up and doing it, over and over and over again, like a song on an endless loop. It can very well make you what you want to be, or drive you to the brink of madness.

It takes waking up every day to the idea that you’re average and ordinary at best, in the hope that one day you will wake up and realise you’re not anymore; that you’re finally a pro. And you know what? Deep inside, you know that it makes no difference, because even superheroes have to practice. So once on top, you’ll still have to go on, and practice. Again. You see, this is the nuts and bolts of getting good at something; in a twisted way, it is a socially accepted brand of masochism, and self-flagellation. “No one has to do this. I don’t have to do it, really, but I’m here,” Miss Compassion said. “And that must mean something. Perhaps I’m getting a kick out of all this.” Lots of kicks actually, like the ones I’m dreaming one day I’ll be able to do. The students on stage finish their form demonstration, and their friends and admirers cheer and clap enthusiastically.

My own group – Taolu Group Number Nine– has some Kung Fu misfits; a kid with a huge pair of thicker-than-average specs, another with a thicker-than-average brain, one who’s significantly overweight, and one who looks anorexic to balance things out. There’s one who’s completely withdrawn and one who’s terribly coordinated, yet oddly comfortable with his shortcomings. That last one is the class clown.

Every group has its share of people who shouldn’t, by any means, belong in a Kung Fu school, but they stay, and surprisingly still proclaim their love for the sport that they so suck at. And maybe that’s really what it takes. Perhaps at the core, it’s not about dragging yourself to the training hall every single day (although that helps too), but about staying. It’s about continuing to suck, until you don’t. And enduring all the odds the world throws against you, while refusing to budge.

- Previous Article I Got Banged!

- Next Article Dalia Does…Feminism