Room to Ponder

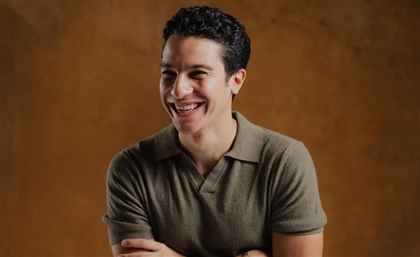

This week our bookie monster takes on Emma Donoghue's harrowing novel, Room, arguing that the story speaks volumes on human nature and the power of perseverance.

We tend to take our freedom for granted. I’m not referencing political revolutions, social activists, or the more media-happy notions of freedom; rather the liberties of life that present themselves in the context of the everyday. In less abstract terms, I am talking about celebrating the fact that I can wake up in the morning, take a stroll to a nearby coffee house, call upon a friend to join me, and engage in fruitful conversations involving trivial gossip and sweet nothings. I realise that unless you’re a Care Bear or one of the Brady Bunch, these might not be things you ponder upon so intently. And seeing as I too am unfortunately not a Care Bear, what demanded I consider all of the above was a story so hauntingly unsettling, and so carefully crafted that I was left in a daze of discomfort from cover to cover.

Emma Donoghue’s novel, Room, is inspired by the Fritzl case that hit news headlines back in 2008. The case involved an Austrian man who held a woman captive for 24 years in the basement of his house. He repeatedly raped and abused her, resulting in the birth of seven children. Three of the seven were raised by Josef and Rosemarie Fritzl (the captors), while the other four joined their mother in captivity. Donoghue, fascinated by the harrowing tale of lobotomised liberty, used the case to inform the plot of her novel. The story is told through the perspective of a five-year-old boy, Jack, who lives in a single locked room with his mother.

While one might anticipate a certain realm of redundancy insofar as how the plot might proceed in telling the daily lives of a mother and child who is born in captivity, what Donoghue taps into through an acute and raw understanding of language and the human condition to persevere, gives rise to a startlingly original and heartbreaking story.

“It’s Jack’s birthday, and he’s excited about turning five. He lives with his Ma in Room, which has a locked door and a skylight, and measures 11 feet by 11 feet. He loves watching TV, and the cartoon characters he calls friends, but he knows that nothing he sees on screen is truly real – only him, Ma and the things in Room. Until the day Ma admits there’s a world outside…”

One of the most striking stylistic aspects of Room is the way in which the narrator, Jack, refers to inanimate objects as living things; offering them names. For example, he does not call his surroundings “the room”, rather “Room.” Similarly, he calls it “Duvet” instead of “the duvet.” Every object in the room ceases to be objectified as it would be in the real world, the way you and I understand it. The use of personalising inanimate objects through viewing them as interactive entities speaks volumes on the nature of the boy’s captivity, and his means of constructing a paracosm that is informed by the only reality he has ever known.

Furthermore, the choice of prescribing a five-year-old child as the narrator of the story lends itself to facilitate the construction of a language so simple and an imagination so willing to adapt that the narrative establishes an incredibly profound impact on the reader. The fluctuation in the behaviour of Jack’s mother, as told through him, gives the reader a clear insight into the adult’s inability to fully adapt and maintain sanity within her predicament. Some days she is engages with her son in a typical mother-to-son manner, involving reading books and studying nature through the television. But then there are times where she is described as spending the entire day in bed, unable and unwilling to communicate with her son.

The story on its own is highly affective, but the stylistic and pitch-perfect ease with which Donoghue taps into the mind of a five-year-old boy who has only experienced the world within the confines of a locked room, propels the novel to a riveting and resonating height.

While reading the book, I felt a sense of claustrophobia that served to pique my curiosity further in terms of empathising and supporting the captive characters. The end product was certainly not a disappointment. As unsettling and horrific as the plot was, I thoroughly enjoyed the unpeeling of Jack’s psyche and character; journeying with him through a roller coaster of tear-jerking naivety coupled with a heart-breaking and precocious imprint on the life of a five-year-old captive. I would highly recommend this book to anyone in the market for a literary dose – which I assume if you are still reading, you are – as I promise a novel story that can be epitomised in one word: unforgettable.

- Previous Article Square Cast Banned from Travel

- Next Article Nomades Land