Hani Shukrallah: From the Heart

Prominent journalist and activist Hani Shukrallah has twice been at the helm of Al-Ahram's English outlets, and twice he's been fired. In a CairoScene exclusive, Dalia Awad talks to the journalist's journalist about pissing off the regime...

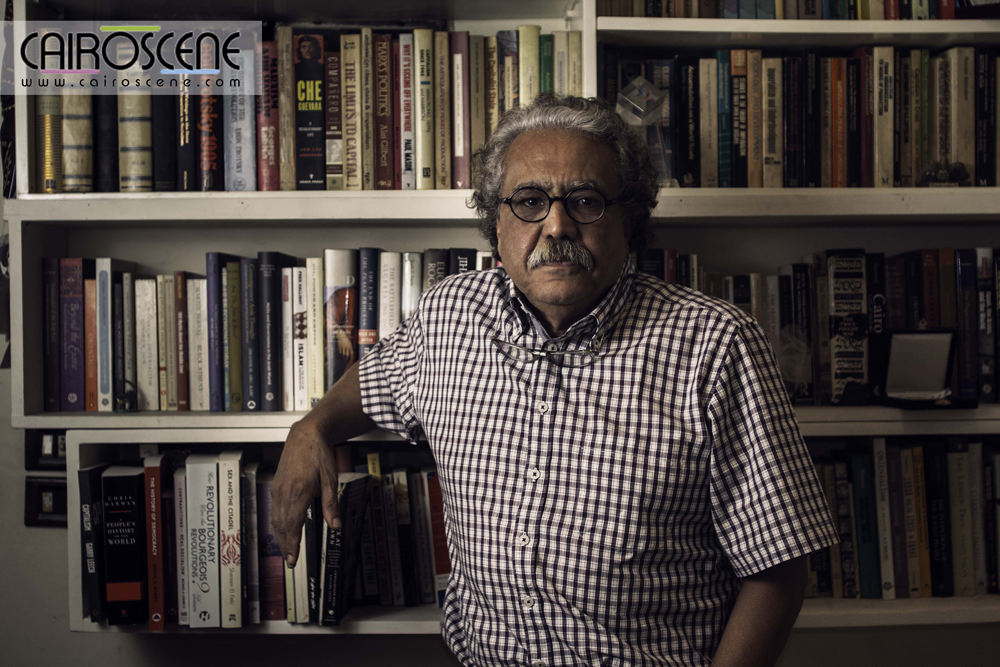

Hani Shukrallah’s studio apartment/office is exactly like you’d expect it to be. Books line the walls, from fiction to philosophy. Family photos stand proudly in antique frames. Ethnic rugs hang vertically, horizontally, diagonally. A television, on mute, keeps him abreast of the country’s developments and an American coffee-maker keeps him up.

At 63, Shukrallah admits he isn’t as energetic as he used to be. Before he rose to journalistic prominence, he was an ardent student activist - often associating himself with a Marxist school of belief - and went on to co-found the Egyptian Organisation for Human Rights. Since then, he’s been appointed and impolitely (and indirectly) dismissed as an editor-in-chief at the English language outlets of Egypt’s most powerful newspaper, Al-Ahram. Twice. Shukrallah may not be as energetic as he used to be, but I bet that in his younger years, this is exactly how he wanted his life to turn out; pissing off the regime from a kick-ass downtown studio apartment/office. What he (and I) didn’t expect is that he’d be sharing that so-hipster-it-hurts space with a tiny kitten. “I don’t remember her name, actually,” he laughs. “My daughter rescued her, then she travelled, so she’s staying with me!”

Grabbing the television remote as we settle down, Hani Shukrallah sighs audibly. “This so-called media... They’re going to be the cause of my third heart attack. Or forth. I can’t keep track,” he says, waving the controller like a green laser at the screen. He’s pointing at one of the many talk show hosts, on one of the many private satellite channels, spouting liberal secularism with unabashed bias. Though these shows arguably fight for the same rights he’s been clamouring for since Sadat’s 70s, and are as critical of the Muslim Brotherhood as he is, it quickly becomes clear that Shukrallah is one of few in Egypt that puts the ethics of journalism first and foremost. So what was a Marxist, human rights activist, media-moral-code-following nice guy like this, doing at Al-Ahram to begin with? How did he end up at the state-owned propaganda machine? “Honestly? I took the job as a favour for a friend. The editor-in-chief of Al-Ahram Weekly was taking a sabbatical. She asked me to cover for her and I ended up staying,” he chuckles, finally switching off the angina-inducing box.

This favour turned into 14-year stint at the English-language weekly, first as managing editor, then as editor-in-chief. A journalist’s journalist, his editorial line was simple: “News is news. If you want to say your opinion, then write an opinion piece.” As such, he pursued both with a passion. In 1995, he started his own column, which was sprinkled with criticisms of Mubarak’s regime, as he continued to shed light on the restrictions on human and civil rights in Egypt. At the same time, he began covering events that were largely ignored by the main newspaper – small demonstrations “where 100 protestors would be met by 1000 police men,” and opposition movements. This bold combination would not go unnoticed, of course, and though “English press could get away with more because it usually slipped under their radar,” Shukrallah would often get calls and memos from the chairman of Al-Ahram’s board, as well as high ranking government officials. “I’d feed them all the same lines,” he remembers. “I’d tell them that our readership were sophisticated and highly-educated Egyptians and foreigners in the country, neither of which would accept the same kind of content the main newspaper was putting out. Which was true. What wasn’t true were my promises to tone it down.”

“Egypt’s political scene had been stagnant for so long, there wasn’t even that much for us to write about that would catch the attention of the government,” says Shukrallah. The turning point, however, was 2005, and it was that very same year that he was dismissed from his position. In the run up to the presidential elections of September 2005, a shift that the government tried its best to keep under wraps began unfolding. Movements like Kefaya sprung up, and those running against Mubarak had, in context, some sizeable support. Of course, Shukrallah and his team did their best to keep their readers informed, while the editor-in-chief’s column entries had much more to inspire them. Despite this, however, Shukrallah could have never guessed that his removal was in the works. “I had no inkling. None!” he yells, comically. “The first I ever heard of it was in some other newspaper. It was a bit of a joke of a newspaper; the type I used to just skim the headlines in, and chuck out. And there was this three-line story that I was going to head-to-head with Assem El-Kersh for the editorship of Al-Ahram Weekly. That was the first I’d heard of it!” This little snippet of news proved to be true, but it wasn’t so much a competition for the position, as it was a direct replacement. But this wasn’t the last the institution would see of Shukrallah. And Mubarak’s regime wasn’t the last to be offended by his work.

Straight off the bat of his unexpected discharge, Shukrallah thrust himself into another intrepid journalistic endeavour by helping found what would later become a pinnacle of the liberal press, Al-Shorouk newspaper, along with four other co-editors-in-chief. “That never really went to plan. Although they tried to give each of us equal say in the editorial line, no publication can have multiple people in charge,” he muses. “Though it was a good chance for me to experience Arabic journalism.” Between 2005 and 2010, Shukrallah continued writing and consulting for many local and international publications and journals, though, in his words, “Egypt was stagnant again.” As 2010 wound to an end, the man with seemingly no plan, would find himself at the helm of Al-Ahram Online – the English news portal we’ve all come to know and depend on today. But why return to the scene of such discontent? “Well, for one thing, I was never officially ‘fired’ per say. You know how these government entities work. It takes something huge for them to fire someone. For bureaucracy’s sake, I was officially on leave without pay,” he remembers, with a sarcastic grin. “I came to hold the position of editor-in-chief of the site with the condition that I would hire who I wanted and work the way I wanted. I didn’t want some member of the board to come along and make me give his niece or whoever a job.”

And so Al-Ahram Online was born – and what a time to come to life. Two days before the November 2010 parliamentary elections, the website went live, and Shukrallah sent his team – “A small team, of well-paid, skilled journalists, rather than how the main newspaper is made up of hundreds of low-paid not-so-great reporters,” – out onto the streets to cover every action. “It wasn’t long before I was receiving the same calls I had at Al-Ahram Weekly, telling me to tone things down, especially as this time the stories we reported had a wider impact with the foreign media. We’d publish an article that said there was alleged forgery at so-and-so ballot box, and the foreign journalists would all head there!” Though he was probably as blasé and matter-of-fact about these phone calls from above as he is now in retrospect, his family showed concern, albeit sarcastic: “My wife would always ask me: ‘Don’t you want any friends!?’” Little did Shukrallah and his team know that these events were simply the opening act for the drama that was to unfold just two months down the line.

By January 25th, 2011, Shukrallah was unfortunately recovering from his second (or third) heart attack, though what he saw on his television screen sprung him into motion. He and his team worked around the clock to cover Egypt’s spring, though he wasn’t the whip-cracker you’d expect an online editor to be as unprecedented action unfolded around them left, right and centre (trust me, I know). Instead, he wanted his team to “experience what was happening. Because it was happening to all of us. I knew from the moment I saw, for the first time, more protestors than policemen... I knew this was different and we all had to be a part of that.”

For 18 days, they stuck it out, balancing emotion with their mandate to inform. When it came to the 11th of February and the world waited for Omar Suleiman to make the speech that would send Egypt into a blaze of euphoria, Shukrallah insisted that he write the article to announce Mubarak’s resignation himself. “Then I sent everyone out. It was time to stop working and start celebrating.” Under SCAF’s rule - and eventually under Morsi’s - Al-Ahram Online became the go-to source for everything happening in Egypt. And, for once, there was a lot happening. “Stagnation wasn’t a problem anymore!” he laughs as he recalls the incredible click-rates the site has had ever since. “It’s about a million unique users a month. And the majority is split pretty evenly between Egyptian and American visitors. Sometimes the USA is in the lead, actually,” he explains, letting us in on the huge role the portal has had to play in the reporting of Egypt’s events, globally.

When Morsi was elected in 2012, Shukrallah expected that his days would be numbered. Still speaking out against the regime, perhaps even louder than he’d done in Mubarak’s time, he watched the political scene closely, made sure Al-Ahram Online reported it to the tee and waited for the inevitable. “The Islamist-infused Shoura Council went about Brotherhood-ising Egyptian institutions, from small rural villages to, of course, the state-owned media, but they tried to do it in a much sneakier way than Mubarak and his cronies,” he explains. Rather than approach Shukrallah head-on, the new Chairman of the Board, Mamdouh El Wali – an Islamist-sympathiser – went about silencing the man who had rattled more than a few cages by attempting to humiliate him. “They cut my salary in half. Then they cut it again. I didn’t say anything, though. Politics are politics. I didn’t want things to get personal. If I asked for that sort of favour, I was sure I’d have to repay it somewhere down the line and that would compromise the integrity of everything we’d worked so hard to build,” he recalls. “Whenever anyone asks me about him, to this day, all I say is that we were classmates back in our university days.”

Hani Shukrallah was officially pushed out of his position by an arbitrary decree which forced chief editors into retirement at the age of 60, rather than 65, but not before he would feel the wrath of the Muslim Brotherhood’s “e-militias.” “You would see the same exact comments, with maybe a word or two changed here and there, across the site, and on my articles especially. I can only imagine a room filled with Muslim Brotherhood members typing away furiously day and night!” That’s not to say he didn’t have fun with it. “I like to be a bit silly on social media! Each of my Tweets gets a bunch of these pre-written replies, so I like to push them and have a laugh.” And my, does he laugh.

For a man who wants nothing more than that fundamental freedom of expression to be ingrained in the minds of every Egyptian, ruler or ruled, being stripped of all that hard work must not have been an easy experience, not least when it happens twice. But ‘easy’ is the perfect word to describe Hani Shukrallah, who, as we wrap up our conversation, answers a call to finalise dinner plans with his ex-colleagues, cracking jokes at every interval. This is a man who sees the silver lining in every dark cloud and is not only brave enough to weather the storm, but does it with his heart on his sleeve, so everyone can see it’s still beating to the same drum it was when he began this journey. And after three (or four) heart attacks, that’s a pretty courageous place for it to be.

- Previous Article I Got Banged!

- Next Article Nomades Land