Learning From The Original Economists

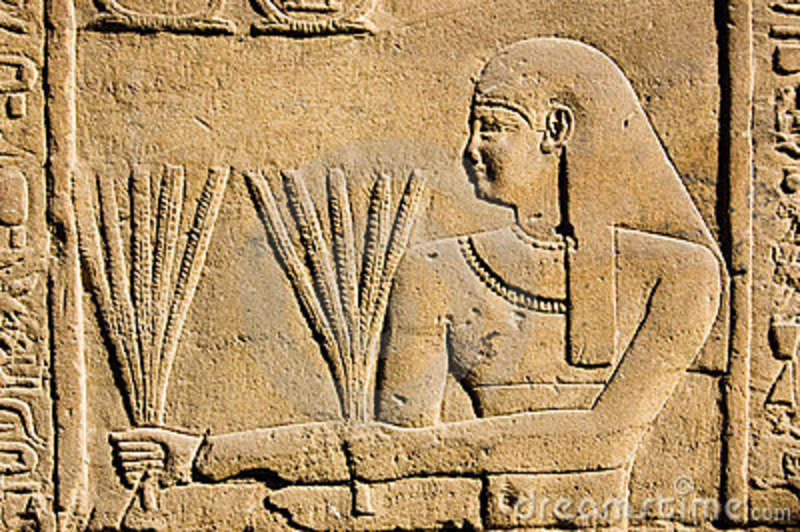

Two articles in The New Yorker and Forbes suggest that there are major parallels and comparisons to be made between Ancient Egypt and modern times, in terms of economic practices.

Proving that Ancient Egypt wisdom and parallels have no expiration date, an article in The New Yorker by John Lanchester that was reworked by Steve Denning, a Forbes contributor, suggests that today's economic leadership could learn 7 lessons from Ancient Egypt that could help bring the economy into a new golden age.

The most important economic event that took place during the times of the Ancients was the annual flooding of the Nile floodplain, which dictated the agricultural economy for the year. At the time the most powerful people, aside from the Pharaoh, were priests who conducted elaborate ceremonies predicting the coming year's flood. Just like economists have various indicator tools to explain the state of the market, Priests had their own tools to predict the flooding outcomes that was only accessible to the priesthood.

According to Lanchester, “they had something else, too: Nilometers. These were devices that consisted of large, permanent measuring stations, with lines and markers to predict the level of the annual flood, situated in temples to which only priests and rulers were granted access… They helped give the priests and the ruling class much of their authority.”

Denning’s articles breaks down Lanchester's piece into 7 lessons that apply to economists today.

Lesson #1: Economic priests reverse the meaning of words

Today's economists have redefined all the keywords and given them opposite meaning, in a process Lanchester calls 'reversification'. “Credit” has been “reversified”. Instead of the positive meaning of the trust in and reliance on the truth, it now means the acquisition of a financial liability. “Inflation” and “Synergy” also now have opposite connotations, among many others.

Denning compares this “reversification” to the Ancient priesthood who were the only one that could access the knowledge of the Nilometer, meaning they were the only people who can speak of money, as they were the only ones who could understand the terminology. The lesson learnt is that people will never be able to comprehend their economy for themselves without first understanding the language.

Lesson #2: Personal Nilometers are not practical

Lanchester asks if it is even practical “to measure the level of the Nile for ourselves? Just like the ancient Egyptian didn't have access to the Nilometer, today's citizens lack access to the information to understand what is going on in the financial sector, but even if they did they wouldn't be able to understand what it means. Otherwise the 2008 global economic meltdown that started in America, would have been easily solvable, but wasn't due to the vast complexities and the shady dealings that only few could pretend to understand.”

The concept of too big too fail, and too complex to understand is why Denning concludes there is no way that individuals can have “personal Nilometers” to understand and monitor large-scale activities deliberately conducted in secret.

Lesson #3: The economic priesthood is not all bad

One could argue that both economists and priests are needed in their respected times. However, as John Lanchester points out, it’s difficult to keep the activities of the financial sector in perspective: “Most of the writing on these subjects was done either by business journalists who thought that everything about the world of business was great or by furious opponents from the left who thought that everything about it was so terrible that all that was needed was rageful denunciation. Both sides missed the complexities, and therefore the interest, of the story.”

Lesson #4: Understand the big picture

The biggest difference between ancient Egypt and today's reality is that Egyptian society was remarkably stable for thousands of years, whereas the economy today is always in flux.

The reason Egypt was able to stay stable for so long is because of its priests who primary function was to preserve that stability, while conversely economists today are all about protecting their wealthy investors who expect outsized returns, resulting in over-investment and bursting temporary bubbles created.

Lesson #5: The status quo is hard to change

Both the priests and today's economists are afraid or relinquishing their powers, even in the face of stagnation or collapse. The sad truth is that today's stock market is disconnected from reality, and very seldom reflects the actual state of the economy. For economists today it is all about appearance and not the reality, as appearances are sufficient to make the stock market soar. It is for this reason that Denning concludes that both economists and priests themselves would rather believe in their own myths, than find a better way forward.

Lesson #6: Progress depends on proactive officials

Building on the last lesson, Denning argues that both priests and modern day economists are too stubborn in their ways. Nowadays those responsible for regulating end up acting like cheerleaders of a system they don't understand. There is a tendency for regulators to become too complacent and accepting of the status quo of the businesses they are supposedly regulating.

Lesson #7: Disentangle the myths and rituals from the reality

Irrespective of the historical period, maintaining myths is counterproductive to progress. It happened with the priests who were stuck in their ways, and it is happening to economists today. Like the myths and rituals of the priests of ancient Egypt, shareholder value theory is laced with religious overtones. Shareholder value remains pervasive in business, even though it is responsible for massive offshoring of manufacturing, thereby destroying major segments of the US economy, undermining US capacity to compete in international markets and killing the economic recovery.

- Previous Article Amina K. Wins Award From British Council

- Next Article Nomades Land