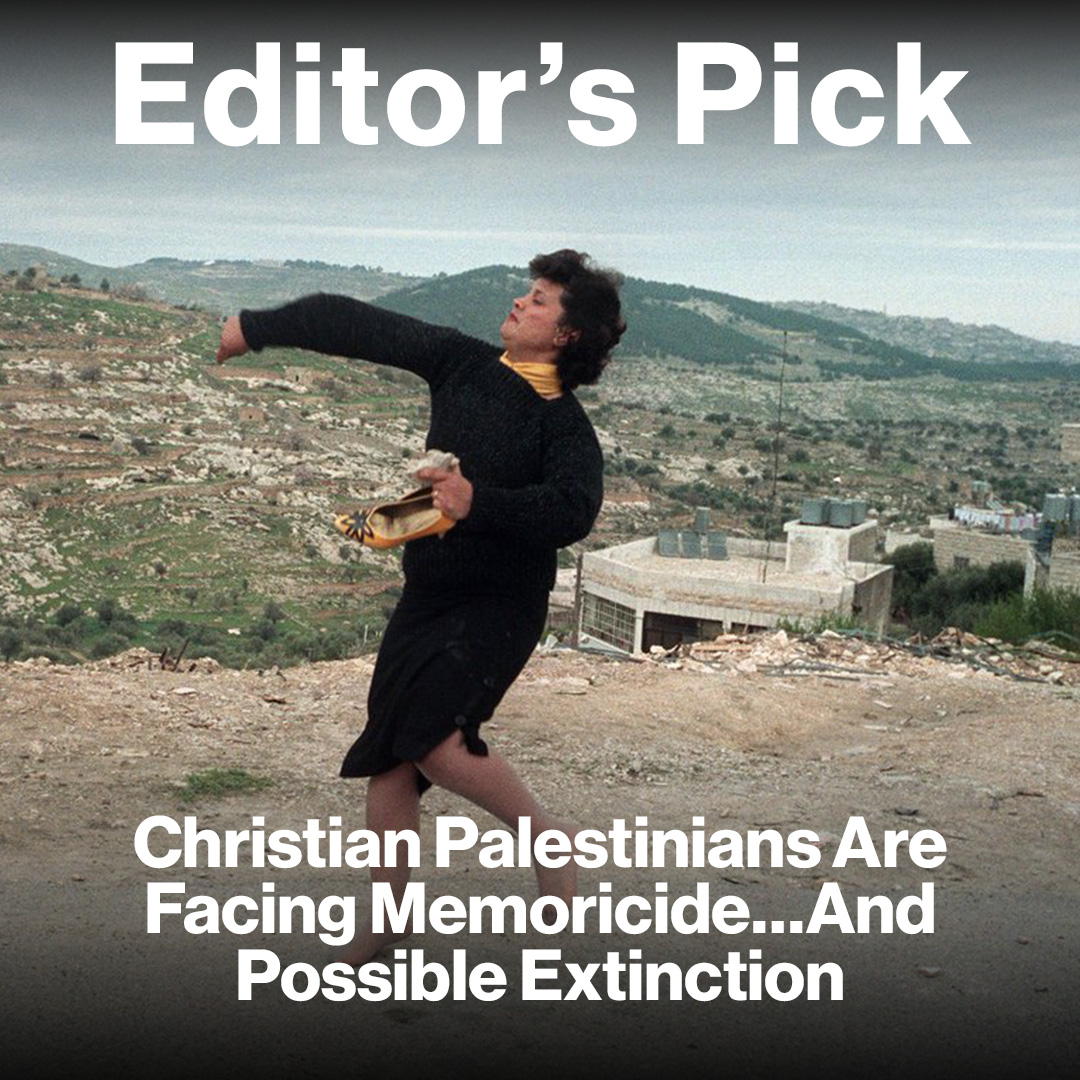

Egyptian Artist Wael Shawky on ‘Drama 1882’ at Venice Biennale

Examining identity, sovereignty and empire, this is the exclusive story behind the musical-film stealing the show in Venice.

It is Friday, the last preview day for press, critics and collectors at the 60th Venice Biennale before it opens to the public this year. The halls of the Arsenale and pavilions in the Giardini are buzzing with excitement - and yet, the queue to the Neoclassical kiosk housing the Egypt pavilion stands out, stretching over 200 metres around the nearby gardens, from the entrance past the coffee stand to the next pavilion.

Inside, Egyptian artist Wael Shawky’s ‘Drama 1882’ exhibition screens a dramatic eight-part operatic film of the same name, scored and directed entirely by the artist himself. It is a feat of determination and hard work; although it was commissioned by the Egyptian Ministry of Culture and the Italian Accademia d’Egitto, the pavilion’s contents were funded entirely through private means, and was coordinated by the artist and his team. The film was professionally produced in record time this year with a cast and crew of almost 400 people, including both professional and amateur actors.

-78fe1bef-5fb1-4c21-aa41-931a402e1f70.jpg) Shawky’s script, sung entirely in Classical Arabic, tells the story of events surrounding Ahmed Urabi’s nationalist revolt against British imperialism in Egypt between 1879 and 1882. Though it started with a simple disagreement outside an Alexandrian café between an Egyptian donkey owner and a Maltese passerby in the first part of the story, that moment sparks a riot between Alexandria’s native inhabitants and the city’s foreign residents, most of whom come from Mediterranean nations like Italy, Greece and Malta.

Shawky’s script, sung entirely in Classical Arabic, tells the story of events surrounding Ahmed Urabi’s nationalist revolt against British imperialism in Egypt between 1879 and 1882. Though it started with a simple disagreement outside an Alexandrian café between an Egyptian donkey owner and a Maltese passerby in the first part of the story, that moment sparks a riot between Alexandria’s native inhabitants and the city’s foreign residents, most of whom come from Mediterranean nations like Italy, Greece and Malta.

Shawky explores the idea of foreign power and identity, at first on a very practical level, before continuing to depict the nation’s descent into a bloody massacre at the hands of British imperialist forces. Headed by Queen Victoria - portrayed by an Egyptian actress dressed in a white gown and petticoat - the empire crushes and occupies Egypt. Shawky ensures that the principal figures such as Queen Victoria and the British-backed Prime Minister Riad Pasha, who like the queen is dressed in white as well, can be identified quickly using the colour of their costumes. Short, on screen subtitles alert the viewer of their historical identity and significance as well. Groups of performers representing the Khedive forces under the British imperial command, many of whom are also dressed in white, go up against the nationalist troops under the young Ahmed Urabi, shown in bright, colourful costumes. Thus, Shawky presents his audience with his characters’ allegiances visually.

“This is not a history lesson, but a retelling of a story that has been taught to school children throughout the Middle East,” a Lebanese journalist tells me. “The stage is set and Shawky draws upon real events, touching upon the motivations of each character, humanising their intentions and also outlining to some extent their absurdity.” The soothing rhythm of the music and the character’s movements follows the drama of a story in which we are given no clear or definitive message or angle.

Shawky encourages his audience to reflect upon the fate of the coloniser and the colonised, just as the biennale’s curator, Adriano Pedrosa, has done through the event’s theme this year: ‘Stranieri Ovunque - Foreigners Everywhere’. The theme invites audiences to consider the notion of foreigners in different contexts.

“The way Wael Shwky relates and plays with histories through building sets and narratives and the way he interweaves theatre, film and art, make him a singular voice in today’s art world,” says Antonia Carver, who has worked in the region for many years as the current Director of Art Jameel and previous director of Art Dubai and Bidoun Projects. Shawky’s interweaving of stories allow him to underline the fortuitous nature of storytelling and perceptions.

Shawky’s other work include ‘Cabaret Crusades’, which features marionettes instead of human actors, and his 2022 film, ‘I am Hymns of the New Temple’, which is also being presented this week at the Biennale in Venice’s Museo di Palazzo Grimani. Looking back at them, Carver reminds me that “his characters are fantastically imaginative yet always somehow familiar and relatable, seemingly against the odds. We quickly become embroiled in their world and complicit in these often undertold and contested histories.”

Shawky’s other work include ‘Cabaret Crusades’, which features marionettes instead of human actors, and his 2022 film, ‘I am Hymns of the New Temple’, which is also being presented this week at the Biennale in Venice’s Museo di Palazzo Grimani. Looking back at them, Carver reminds me that “his characters are fantastically imaginative yet always somehow familiar and relatable, seemingly against the odds. We quickly become embroiled in their world and complicit in these often undertold and contested histories.”

‘I am Hymns of the New Temple’ is set in Pompeii and features actors wearing dramatic handmade masks. As Carter says, the film explores the histories and mythologies of a town only known through the vestiges of its destruction by the volcano at Mount Vesuvius in 79 CE.

“I am giving absolutely no answers,” Shawky says, when I catch up with him outside the busy pavilion. “It’s all about analysis.” He explains that giving too much away to the viewer risks losing the meaning of an event or a story. I ask him about his use of marionettes in ‘Cabaret Crusades’: was this a way to distance the audience from familiar narratives? With a grin, he concedes. “Now I decided to make a shift in my career,” he says. “I decided to work with adults and even to call it drama, which I always tried to erase!” He goes on to explain that though ‘Drama 1882’ features adult actors, he wanted to be able to control the effects of the action and the impressions that actors made on the audience. He does this through tight coordination and swaying movement which, according to Shawky, is enough to focus the audience and ensure that the actors do not ‘act’.

“Actors always give expressions and they always try to move in a certain way. I need the expressions to come from the movement, the choreography and the direction.” He goes on to explain the importance of artistic control over the image as a medium to express an idea, saying, “Everyone is being controlled by something and someone.”

“Actors always give expressions and they always try to move in a certain way. I need the expressions to come from the movement, the choreography and the direction.” He goes on to explain the importance of artistic control over the image as a medium to express an idea, saying, “Everyone is being controlled by something and someone.”

“But it is not just the control of the work,” Shawky adds. “When I received the invitation from the government to present Egypt, I said in order to be able to do this I have to have full control over the pavilion otherwise I cannot achieve it. I don’t want to go through the censorship bureaucracy. I don't want to go through any of that at all. They were very nice to me and the government gave me the freedom to do it.”

To do so on such a massive scale took dedication and a refusal to compromise. Shawky and his team raised most of the necessary funds necessary for this important project through fundraising in Egypt. and the remaining amount of the production bill was footed by Shawky’s four galleries: the Lisson Gallery in London, the Lebanese Sfeir Semler Gallery, Lia Rumma Gallery and Barakat Gallery.

Shawky’s choice of the Urabi revolt and his historical research is significant in its relation to Pedrosa’s biennial theme, going beyond the country’s own colonial history. ‘Drama 1882’ as an exhibition highlights the notion of the foreigner and foreign discourses that have evolved and changed over time in Egypt, in the Middle East and globally, particularly in relation to the journeys of refugees in small boats – images of which are taken up in Shawky’s drawings and installations along the other walls of the Egypt pavilion. With a massive glass panel, made up of colourful glass moulded using a complicated lost wax method, Shawky has created a tiered relief that portrays the layering of Egypt’s history. Images of the storming of a fortress or town seem to portray the Battle of Tell El Kebir in 1882 when the British defeated the forces of Urabi in the final part of the Anglo British War.

Shawky’s choice of the Urabi revolt and his historical research is significant in its relation to Pedrosa’s biennial theme, going beyond the country’s own colonial history. ‘Drama 1882’ as an exhibition highlights the notion of the foreigner and foreign discourses that have evolved and changed over time in Egypt, in the Middle East and globally, particularly in relation to the journeys of refugees in small boats – images of which are taken up in Shawky’s drawings and installations along the other walls of the Egypt pavilion. With a massive glass panel, made up of colourful glass moulded using a complicated lost wax method, Shawky has created a tiered relief that portrays the layering of Egypt’s history. Images of the storming of a fortress or town seem to portray the Battle of Tell El Kebir in 1882 when the British defeated the forces of Urabi in the final part of the Anglo British War.

Beside the relief is a massive baroque wooden dresser, similar to one that might have adorned the home of a member of the country’s ruling and imperialist classes. Instead of displaying expensive and imported Limoges porcelain or Baccarat crystal, however, the case is filled with dried lima bean - or foule, as they are known in Egypt. The basis of many popular Egyptian dishes, this humble staple symbolises the shifts in power during the events of 1882. Nearby, a massive sculpture depicts a humble earth house, representing perhaps the homes of poor Egyptians in rural areas, atop sharp, spidery legs that appear to be moving away from the historic screen.

I wonder whether Shawky’s work is a reframing of the past or a call to action. I ask him about the importance and significance of the artworks around the central screening. “The objects have to do with dimensions,” he tells me. “I always like projects with several mediums in everything. Each medium for me has its own capability and its own access and limitations. What you can make with drawings, you cannot make with a film. The drawing is giving you a dimension for the topic that you would never be able to access with film. You need as many angles for the same topic as possible. You need to feel and sense the mud and the soil – you cannot sense it from the film alone. You need to get it from the sculpture. So each material has its chemical content even to express something to you for the same topic. Everything has to be like this.”

I wonder whether Shawky’s work is a reframing of the past or a call to action. I ask him about the importance and significance of the artworks around the central screening. “The objects have to do with dimensions,” he tells me. “I always like projects with several mediums in everything. Each medium for me has its own capability and its own access and limitations. What you can make with drawings, you cannot make with a film. The drawing is giving you a dimension for the topic that you would never be able to access with film. You need as many angles for the same topic as possible. You need to feel and sense the mud and the soil – you cannot sense it from the film alone. You need to get it from the sculpture. So each material has its chemical content even to express something to you for the same topic. Everything has to be like this.”

I speak to people emerging from the pavilion and many of them use words such as powerful and mesmerising. Though many were not familiar with Egypt’s history under occupation, they all seem to understand the importance of what they have just seen and the need to question versions of history, more generally. Hwasun Barakat of Barakat Contemporary, a gallery based in Seoul, South Korea, is one of the galleries involved in the funding of the pavilion. “This film is an absolute phenomenon and a high mark in Wael’s artistic career,” she tells me after a screening. “It is mesmerising, and yet empathetic with the shared history, that reminds me of ours in South Korea.”