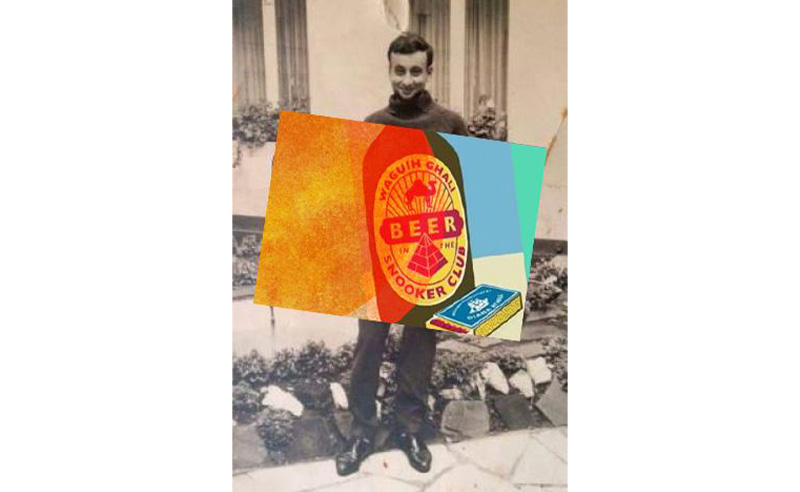

The Redemption of Waguih Ghali: A New Reading of His Life & Works

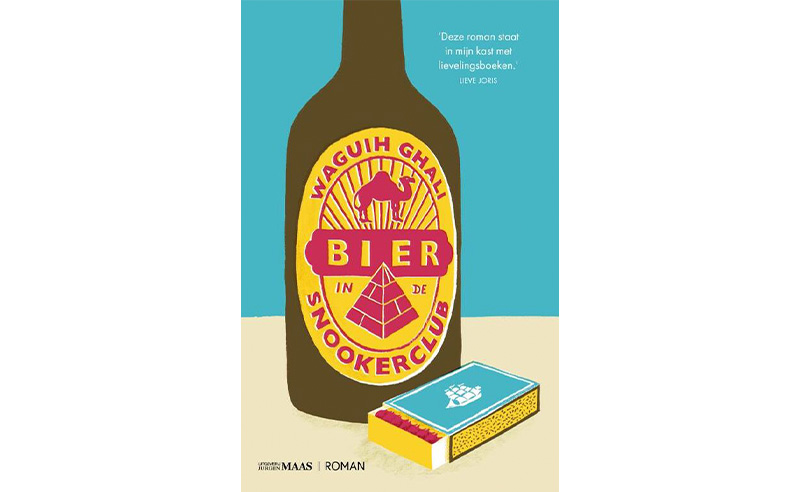

Ghali is best remembered for his only novel ‘Beer in the Snooker Club’, as well as his tragic diaries recounting his exile.

Waguih Ghali was the author of the first published English-language Egyptian novel. His 1964 ‘Beer in the Snooker Club’ is at once a humorous and serious recounting of the first days of Nasser’s Republic. Long before the Arab-English novel became a commonplace genre in world literature, and Arab diaspora voices conveyed the nuances of life in the Middle East to a broader global audience, there existed a witty, avant-garde and little-read novel springing from the pen of an exiled, dissident Egyptian aristocrat.

The novel described contemporaneously the era of the Nasser administration, the newly un-landed aristocracy, the freshly raised class of apparatchiks and generals, the dying of the old multi-ethnic, religiously and linguistically diverse Egyptian metropoles, and the renaissance of the dignified fellah, the peasants of the countryside. Between scenes of childhood best friends chugging beers at Groppi’s and contemplating sarcastically the new realities of the Republic, and melancholic lounging at the Gezira Club’s Lido amongst Eastern European nannies and French-pensionnat educated Pashas’ daughters, ‘Beer in the Snooker Club’ took readers for the first time into an Egypt on the cusp of a great rebirth.

It is the story of Ram and Font, two sons of the old aristocracy who have foregone their family’s politics of monarchism in favour of a cosmopolitan communism in the mode of the Parisian and London left. Ram, sardonic and playful, witty and observant, immersed in two worlds - the vanishing upper class and the rising proletariat - narrates a tale of intense love, hopelessness, friendship and listlessness. This Ram however, was a mirror of the deeply complex, often morose and ever charming character of its writer, the equally notorious and revered Waguih Ghali.

His only published novel, essentially, is as much a grappling with his identity, as it is a moving tale of romance. During a spat with his Jewish lover, Edna, the spritely Ram contemplates his place in the new Egypt. “What am I then, if not Egyptian?” Ram implores Edna. She responds, “You are what you are; and that is a human being who was born in Egypt, who went to an English public school, who has read a lot of books, and who has an imagination. But to say that you are this or that Egyptian, is nonsense.”

Groppi's bar, one of the best places to drink in according to Ghali

Groppi's bar, one of the best places to drink in according to Ghali

This profession of identity confusion was as much a theme in Ram’s life as it was in Ghali’s - educated with Omar Sharif and a host of aristocratic boys at the famed Victoria College. A member of the esteemed aristocratic Coptic Ghali family (of Boutros Ghali fame), Ghali the writer suffered from a worldly cosmopolitanism springing from his Francophone home and Anglophone education, which he often felt disconnected him from the lives of his compatriots. On this alienation of Ghali’s, a scholar of his life and works Doaa Ibrahim writes, “Although the language Ghali uses is English and the book gets published in England, his concerns are specifically Egyptian. Egyptian politics, Egyptian nationalism, Egyptian cosmopolitanism, Egyptian–British relations, and their effect on Ghali’s own identity crisis that finally leaves him crushed.”

Waguih Ghali was born in Cairo in the late 1920s in a milieu of the elegant, gilded beau monde of Cairo and Alexandria. Egyptian writer Ahdaf Soueif describes him as being “the one penniless member of a very rich family.” This life of patronised good-living is well described by the impecunious Ram who drinks at all the city’s finest bars, and gets his suits cut at its most fabled tailors, with the tab being picked up secretly by an unnamed family member or more well circumstanced friend. Ghali’s personal life was much the same, straddling jobs as a sometime factory worker, dockworker and bureaucrat. His life was a constant managing of debts incurred by his two great vices, drinking and gambling. As Ram professes proudly, “I just like to gamble and drink and make love and no matter what act I put on, you should know the truth.”

Ghali the writer’s vices belied a darker shadow-character, a man who struggled with respecting his lovers thus always costing him his companionships, an artist grappling with his place in the literate world, an Egyptian who felt he had no place in the country that Egypt was becoming, a bohemian enamoured with an imagined proletariat, and a socialist at odds with his aristocratic self. The latter issue became of crucial importance to Ghali’s life, when, as a communist activist in a Nasserist Egypt which did not tolerate that ideology, he fled into political exile first in Germany and then in London. It was as an impoverished dock worker in Germany, living in a basement with no heating, that ‘Beer in the Snooker Club’ was composed - a reflection of a life lost, a memoir of a yesteryear that had been fleeting and beautiful, and a fiction on a non-fictional array of realities.

Ghali’s story mirrored that of Russian writer Boris Pasternak - both authors of widely popular novels describing the ineptitudes of reform after large scale social and political revolutions, and both despised by their governments and their peers in their respective cultural scenes. In 1958, Pasternak published ‘Doctor Zhivago’, his epic, classic tale of romance, revolution, human relationships and the poetry of the lands and cities of Russia. Critical of the Bolshevik Revolution’s outcomes, but celebrated both inside and outside the USSR as one of the most moving descriptions of Russian life, the novel was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1958. The novel and Pasternak were banned by Soviet censors, and Pasternak was unable to collect the prize and had to reluctantly publicly decline its acceptance. In describing his despondency and alienation after being ostracised by the cultural scene in the USSR, he wrote his now-classic poem ‘Nobel Prize’, of which one stanza reads:

“Am I a gangster or murderer?

Of what crime do I stand Condemned?

I made the whole world weep

At the beauty of my land.”

Ghali too “made the whole world weep at the beauty of his land,” and through that experienced the pain, alienation, suffering and exile which accompanied numerous artistic talents speaking truth to power, and maintaining an honest expression whilst dwelling in the fascist experience.

The alienation and despondency experienced by Ghali was most acutely spotlighted in his diaries. Whilst in an impoverished political exile in Germany, Ghali began keeping his now infamous diaries. Published for the first time in 2017 by the AUC Press, the diaries shone a light for the first time on the troubled, tragic, hostile internal world in which Ghali dwelt. It is awash with tales of his drunkenness (almost every entry), his gambling addiction, his bad ways with his lovers, and the deep, unidentifiable melancholy that often took hold of his entire person - and which would ultimately lead to his 1969 suicide. “The diaries reveal Waguih’s self doubt and his self-destructive behaviour, as well as his depressive tendencies. He drinks heavily,” Deborah Starr, a scholar of Ghali, tells CairoScene.

In 1966, Diana Athill, the London-based editor of Ghali’s novel received a troubling letter from him: “Get me to London. This place [Germany] is killing me. If I have to stay here I can’t not kill myself.” After editing ‘Beer in the Snooker Club’, Athill became a close personal friend and sometime lover of Ghali’s, and immediately agreed to sponsor Ghali’s move to London as well as host him in her London home. It was during these last three years of his life that Athill learnt how troubled Ghali really was - a story she would compile and publish in her memoirs of their time together entitled ‘After a Funeral’.

The book, unkind, unsympathetic and stereotypically British in its unfeelingness, describes an uncharming, uninteresting and cruel man. Although the book’s merits may be critiqued, it survives as one of the few if not the only external narration of Waguih Ghali the man. It is regrettable that this book became the most widely held perception of Ghali’s character - whilst it eschewed his visionary literary voice, his profound observance of the Egyptian and greater human condition, and his obvious immense passion and joie de vivre so expressly explained in his novel, Athill’s book created out of Ghali a fictitious villain after he had already taken his life and was unable to defend his own character. Deborah Starr comments on ‘After a Funeral’ that “it is definitely reflective of Ahtill’s own perspective, and is centred on her interactions with Waguih. The text is often demeaning of Waguih and his family members. I find it interesting to read alongside the diaries for the ways they intersect or contradict. But, I fundamentally don’t put much weight on Athill’s ‘After a Funeral’.”

For decades, this version of Ghali held in the minds of the public, until his own description of his struggles was brought to light after his diaries’ publishing. In a damning review of ‘After A Funeral’ in the London Review of Books, Ahdaf Soueif denigrates Athill’s character assassination of Ghali, writing, “She shows us an obsessive drunk, an egocentric who battens on people, hurts and reviles them, and who bores them, and us, beyond all permissible limits. The saddest thing about this sad book is that, for all Miss Athill’s protestations about her subject’s charm, intelligence, courtesy, wit and attentiveness, these qualities never come through. In order to place any value on this short life, one has to turn away from Miss Athill’s ‘Didi’ [Ghali] to the self-portrait in Ghali’s now out-of-print ‘Beer in the Snooker Club’.”

As Athill’s rendition of Ghali’s character was his overarching legacy in the Anglophone world, in his native Egypt Ghali was remembered more sinisterly for a very long time. In 1967, following the war between Israel and various Arab states, Ghali visited Israel as a journalist to document how the aftermath of the war was being remembered in that country. While writing from there, he described the oppression that the settlers were inflicting on Palestinians, and predicted that East Jerusalem and the West Bank would be annexed by Israel to allow for more Jewish settlement. He was to be proved correct.

In spite of his visiting of Israel as a journalist, under Egyptian law even entering an Israeli embassy during the state of war was treasonous. At a public talk given in London upon his return from Israel, a delegate from the Egyptian state stood up and stated that, “Mr. Ghali is not an Egyptian. He has defected to Israel.” Ghali was thus publicly stripped of his nationality. Ahdaf Soueif noted in 1986 that this is “one thing which has stayed in the minds of the very few people who remember [Ghali] today in Cairo.”

Ghali, the complex, the morose, the joyful, the observant, for all of his flaws, deserves to be remembered in the annals of history for his erudite and precise and cutting narrations of the truth of the Nasserist era, both as a political as well as a literary figure. His novel survives today as a poetic description of the Egyptian soul, modern Egyptian history, and the power of the jokes and humour which have lightened the historically burdensome load of the country’s average citizen since time immemorial. He was Egypt’s own storytelling playboy Pasha-cum-bohemian intellectual-cum-socialist flaneur. His only surviving novel is a jewel in modern world literature, and a gift to any reader interested in the ways in which Egyptians express joy in times of turmoil.

The opening epigraph in ‘Beer in the Snooker Club’ is a quote from Dostoyevsky’s ‘Notes from Underground’, and reads, “Rather we aim at being personalities of a general… a fictitious type.” It is true. Ram is as real as Ghali is fictitious, and Ghali’s tales are as profound as Ram’s narration.

- Previous Article Italian-Palestinian Duo No Input Debuts Eponymous Electro EP

- Next Article Travel Across History on Egypt's Most Iconic Bridges