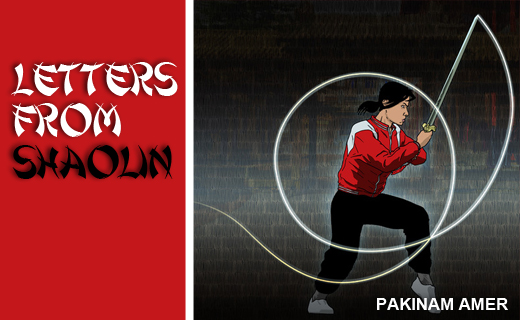

Xiaolong’s “Faithful” White Boy

Faith is one thing but fanaticism is another. Pakinam Amer comes face-to-face with a man who questions her motives.

At the end of April, I was greeted with what I initially regarded as a pleasant surprise: a fresh English-speaking foreigner who has just arrived in Xialong. Tiberias, an Austrian, is a tall sturdily-built 21-year-old who intends to spend the next year learning Kung Fu. When he arrived he was slightly timid, and in the initial phase of panic, reminding me with myself when I first arrived here.

When I met him in the dinning hall, he looked relieved to have met another foreigner. Because of the language difficulty and the strangeness of Chinese culture to outsiders, it often feels as if on one end of the Earth there’s China, and on the other there’s the rest of the world. All foreigners come from one huge country, and the Chinese, well, they all come from this remote island called China.

When my Shifu (Kung Fu teacher) saw how warmly I greeted an American classmate – the first non-Chinese I had run into when I first arrived at the school – he murmured that “foreigners seem to like only other foreigners.” He couldn’t get it. And the statement has some truth, simply because in China it’s just easier to deal with another foreigner than with a Chinese living in the mainland; a region that seems sheltered from the rest of the world, harbouring a distinctive yet odd flavour and culture. Foreigners are also regarded in the same way by many Chinese — we’re all one people, who come from a land far, far away.

After asking where I’m from, Tiberias—the blond Austrian student who doesn’t eat pork “because it says so in the Bible”— quickly asked, “Are there any other white boys?” He chuckled. Intuitively, I knew that he was in fact serious; he really wanted the reassurance that he wasn’t the only white boy. And I gave him that, telling him about John, the American and Chris, the Aussie.

Tiberias had never done Kung Fu, and before the ice was broken, he threw in the question, “Are you crazy to come here alone? All this way to learn Kung Fu? And you’re a girl.” I made a mental note to never assume that all Europeans or “Westerners” (for lack of a better term) are as open-minded about females being slightly eccentric as I’d like to think they are. My bad! “Well, I need a break from work, and I like Kung Fu movies, so it made sense,” I quietly responded. He smiled, and said in Austrian-accented English, “Yeah, me too. I love Kung Fu movies.”

I’d realised that every time someone asked me why I came here, I gave a slightly modified answer. Always a new response. It all made me wonder if I knew the real reason myself. Perhaps if I hadn’t come here, I would’ve lost my mind back in Cairo. I felt a desperate need to disengage. The desire to flee — albeit with a bang and a bit of flare — was eating me up.

If you must escape, don’t run off to the next town, I thought. That’s just boring. If you’re doing it anyway, if you’ve resigned your will to it, you might as well glue on a pair of wings and fly to the moon. We chatted about the food, and I told him how I got used to it, and actually craved it after initially finding it strange-tasting. He wondered about the small strips of meat in the vegetable dishes, and I explained that it’s pork. He said he doesn’t eat it —and I have to admit he’s the first Christian I meet who believes pork is forbidden by the Bible. I said that as a Muslim I usually don’t eat it either, but since there isn’t enough protein in the meals, I make exceptions.

“Ah, you’re a Muslim?”

“I am.”

“Not being a very good role model eating pork like that.”

“Not really, no,” I said, smiling. Long gone where the days when I’d feel an urge to justify my actions. It’s easier to nod, smile and agree.

“So you follow Quran?” Tiberias inquired.

“Yes, but not to the letter.”

“So you kill people?”

“I try not to, but I think about it a lot,” I said with a straight face.

He laughed, then sobered a bit, and suddenly, adopting a more formal, serious tone, he mused: “Those who kill people don’t really follow the Quran. The Quran says don’t kill people, be good.”

Tiberias spoke in intervals, pausing momentarily mid-sentences, seemingly to search for the right English words, or maybe just the right words. After chatting with him for a while I started mirroring this mannerism, pausing between short sentences or enunciating my words for the sake of clarity.

“Yeah,” was the only response I could give. I was reminded how it’s exhausting sometimes to talk about my religion and all the stereotypes associated with it. So I gave brief answers, occasionally just courteous nods. Later that night, and after gulping a few beers, he contradicted that view about the Quran, lecturing me on how the Muslim holy book demanded that believers kill people and “do violent things” if “they occupy a state.” By then, his manner of speaking gained a different momentum. His judgements —about Muslims, Catholics, and those “who don’t follow God in the right way”— reeked of a brand of fanaticism I knew too well.

However, during that first lunch, none of his stubborn beliefs or violent streak immediately surfaced, and after speaking briefly about Islam, Tiberias went on to tell me how he doesn’t follow the Roman Church, and that he believed the Church — as an institution— messes up religion. “They don’t know shit,” he said conclusively. “I just follow the Bible, I’m not part of a group or a movement.”

“I’m not part of a group either,” I said. Suddenly images of Salafis and Brotherhood members (who probably were at each other’s throats politically speaking at the time) flashed into my mind. I shook the vision off, wanting to clear my head of all things past. These images belong back home, I firmly ordered my mind. I’m here now. Only this exists.

I turned away from Tiberias, who sat at my right, and decided to give my attention to my now half-full food tray, picking up the plastic chopsticks and shoveling some steamed rice with tofu into my mouth. Controlling the mind is much easier in this part of the world, I thought.

“What weapon did you choose?” Tiberias’ voice budged in seconds later.

“I don’t use any weapons yet, just my bare hands at this stage. I’m still learning Taolu’s basic forms. Perhaps next month,” I said.

At the time I was only done with my first form — Xiao Hong Quan— and a short second one called Wu Bu Quan. I wasn’t eager to try with Kung Fu weapons. But I didn’t mind training with a stick or a sword. Whips and chains are pretty advanced weaponry, and back then I suspected I’d be striking and injuring myself silly instead of any “opponent” in a real fight with these. My Shifu is specialized in the Jiujiebian — the nine-section chain whip— but I find it awfully scary.

When push came to shove several weeks after that lunch, I started training with the staff, then my Shifu added the broadsword or “Dao” to my routine.

At the end of my lunch with Tiberias, Lucky showed up and asked in broken English if I got my passport back from Border Control. I said I should be getting it next week, hopefully with a 6-months residence permit. When he was gone, Tiberias asked, “Hey, was that guy speaking to you in Mandarin?”

“No, English of course.”

“It sounded like Chinese to me,” Tiberias said.

Amused, I assured him he’ll soon get used to the Chinese accent. I gave Tiberias a hurried orientation, told him where he should receive his uniform, and where to buy snacks between training. I gave him a brief of the training routine and schedule. I left him to make a cup of coffee in my room before the pre-training fast.

It was a short afternoon encounter, but it made me feel that old ghosts can still catch up with you, and that they come back to haunt you in many forms. Tiberias’ manic monologues about God and the state of affairs often made me feel sorry for him, in the same way that I felt sorry for stringently religious friends back home. Conversations with some people are more like spiritual experiences that remind me how healing it is to connect to human beings who’re at once mystified and fascinated by the world and its workings. But not with Tiberias and his likes.

I have been lucky to run into knowledge seekers in this part of the world, people with the right balance of skepticism, curiosity and compassion. Tiberias, meanwhile, seemed to have already formed unwaveringly concrete beliefs about everything around him – something I’ve seen plaguing my own people, the very thing that had once and twice driven me away from my home and my country to seek sanctuary elsewhere.

A month after our first encounter, Tiberias threatened to “smash my face with his fist” and beat me to a pulp when I refused to acknowledge that he’s “the strongest Kung Fu student in the school,” a tall order considering he has the worst technique I’ve seen, and he’s uncoordinated to a disastrously laughable degree. The threat, which was very real, and very unfunny, was the crescendo of weeks of Tiberias trying to convert me to his twisted version of Christianity, or undermining my spiritual inclinations (which include an affinity and a deep respect towards Buddhist and Taoist philosophies), in addition to attempting to convince me that the Big Bang didn’t happen and that the U.S. government is literally in cohorts with the Devil. I simply asked him not to talk to me again, and reported his behavior to the Shifu.

Whoever made the world didn’t assign these people to speak on his behalf, I thought.

That thought and the decision to put my foot down and cast out another destructive behavior (and person) from my life marked yet another departure from that world, where faith, fundamentalism, stereotypes, judgments and anger have painfully spoiled the reality that perhaps we’re here for something more transcendent than word play or wars in the name of God.

- Previous Article I Got Banged!

- Next Article Dalia Does…Feminism