Past Tense Continuous: the Live Reenactment of the Palestinian Nakba

A striking series of photos by Ramallah-based Dima Hourani quite literally stopped us in our tracks, forcing us to question the reality of the Palestinian crisis and bringing painful memories back into the modern consciousness. We speak to the interventionist artist to find out more...

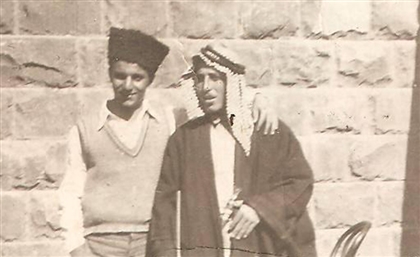

It may look like Photoshop, but look closer: one truck, three families and their possessions, in real black and white. Using water colour paint on the skin, dyed clothes and a painted truck, Ramallah-based artist Dima Hourani recreates memories of the Nakba as she unfolds her interventionist artwork, Past Tense Continuous.

Using a “total sensory experience to create a simulated image in our memories,” in the words of Hourani, the project was implemented last April in Acre, Israel, commemorating the 67th anniversary of the Palestinian Nakba; what Palestinians call the exodus that followed the 1948 Palestine War.

“It is an alternative reality, attempting to appeal to the oral and visual memories, which continue to exist with us until the present day,” the artist says.

The interventionist pieces of art were created as part of Hourani’s research on the Palestinian collective memory of the Nakba: “I used a black and white image of a truck full of people and some of their belongings; an image that has been so often repeated and imprinted in our minds as Palestinians. It is an image of unknown survivors, the story of any Palestinian family, refugees with different ages, regions and fears,” she says.

What if the Palestinian refugees had now returned to their villages and towns, to their homes and fields? What if they had returned to Haifa, Jaffa, Al-Masmiyya and Acre, the artist wonders, as her black and white families walk across the city in a continuous journey that began 67 years ago.

Delving into the collective memory beyond the captured time, Hourani attempts to manipulate and destabilise interpretations when dealing with images, especially images that archived historical events such as the Palestinian ‘1948 catastrophe’. “This project creates a space for intervention into the fantasy behind the story, when what happened did not only happen in the past, but it is happening now,” she explains.

Born in Jordan to Palestinian parents, the 30-year-old artist moved back to Palestine in 1997, after the Oslo Accords were signed between the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) and the government of Israel. These three families “represent all the Palestinian community that was living in that land,” not documented as refuges but as families from the urban and rural life, she tells CairoScene. “The gravity of any image it's not to prove the moment, but the fate of the people pictured,” she adds, poignantly.

Within the same line of thought, Hourani now continues her research, focusing on image subjectivity and its link with communities across different geographical locations. What if their faces, their clothes and their memories went out of those black and white photos that captured all memories? Her project relies mainly on the persuasive power of visual elements, which she puts in motion as a representation of the past as well as a means on reenactment.

“The project is related to the process of searching in the effective memories that added a value to the cultural heritage, which is not linked to a geographical region. Emotions that link to memories, place and time can be characterised with happiness, fear and pride. All of these impacts open a door that allows us to dig deeper into the image’s subjectivity within a specific community,” she adds.

But the project also explores our relationship with technology as a means of recreating and relocating memories, noting the difference between the intimacy of a photograph in the past and the amount of photographs taken nowadays. How can our nostalgia of the past be affected by the use of modern day technology as an attempt to keep the past present?

Thus, the project, the artist says, will be incorporating heritage items of great importance and power attempting to find authentic meaning, as we recognise it. “If we want to know our destiny we should know our roots and as Birgit Meyer said "‘Cultural heritage is not given, but constantly in the making: a construction subject to dynamic processes of reinventing culture within particular social formations and bound to particular forms of mediation.'"

For more information, visit Past Tense Continuous on Facebook here.

- Previous Article The Battlefield is Coming

- Next Article Upper Deck: Sushi in the Sky