Bethlehem’s Only Luxury Boutique Hotel is Now Facing an Empty City

In Kassa, guests are encouraged to be in Bethlehem rather than merely see it.

In Bethlehem, a city so often cast in the sepia glow of biblical nostalgia, where pilgrims trace the same cobbled paths as the Magi and pause before relics venerated for millennia, a small six-room boutique hotel quietly aims to reshape the conventional narrative. Kassa Boutique is a refuge where artistry and history coalesce into something fiercely local, and strikingly contemporary.

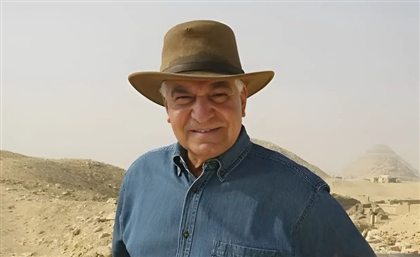

The hotel is the brainchild of two unlikely collaborators: Fadi Kattan, a culinary storyteller, and Elizabeth Kassis Sabagh, a Chilean businesswoman whose family history reads like a microcosm of the Palestinian diaspora itself.

Kattan is the gastronomic mastermind behind buzz-worthy Palestinian restaurants ‘Akub’ in London’s Notting Hill, Louf in Toronto, and the book Bethlehem: A Celebration of Palestinian Food. For many years, Kattan also ran the Hosh al-Syrian guesthouse in Bethlehem’s Old City. His lodgings became a quiet sanctuary for those seeking an experience beyond the well-worn paths of pilgrimage tours, while ‘Fawda’—the little nook of a restaurant inside his guesthouse (and Kattan’s domain)—became a beacon call for travellers weary and wary of superficial claims of tradition and authenticity. The name itself—Fawda, Arabic for literally chaos—was a playful nod to the way the restaurant operated. There was no menu. No fixed dishes. No predictability. Instead, Kattan would roam the souq in the morning, selecting the freshest ingredients, and then build the menu from scratch each day based on what he found. A perfect fig in late summer transformed into a dish with local cheese and honeycomb from the Bethlehem hills. Sadly, the pandemic forced the guesthouse into a forever closure.

But not before Elizabeth Sabagh found her way to the guesthouse, met Kattan, and struck an unlikely friendship that would turn into an extraordinary partnership, with the idea of the Kassa boutique hotel conceived over endless cups of coffee during her visit.

In May 2023, the Kassa boutique hotel was born in the ancestral Sabagh family home, a place rich with the echoes of generations past. The Sabagh family, one of Bethlehem’s oldest and most prominent families, had long been a part of the city’s history, their name woven into the very fabric of its streets and stories. The house, a stately structure of thick limestone walls and elegant arches, had been a private residence, a gathering place, a witness to Bethlehem’s changing tides. It was here, within these very walls, that Kassis Sabagh’s ancestors once lived before dispersing across the world, part of the great Palestinian diaspora.

By transforming the family home into Bethlehem’s only locally owned boutique hotel, Kattan and Kassis Sabagh were not just creating a place for travelers to stay, they were reclaiming space, ensuring that a piece of Bethlehem’s past remained firmly rooted in its present.

But to understand Kassa is to understand what it is not. It is not another somber waypoint on the well-trodden pilgrimage circuit, where history is often quite sanded down to fit neatly into the tour bus-tight schedule. Bethlehem, after all, has long been a city confined by its own mythology. The name alone conjures images of midnight masses and nativity scenes, of frankincense and hallelujahs, of a city perpetually frozen in the act of awaiting something divine. Yet beyond the mangers and the hymnals, Bethlehem is a place of exquisite contradictions; a city where the past is inescapable but never static, where modernity presses in against ancient walls, and where an entirely different kind of visitor had begun to arrive.

“In Kassa, guests are encouraged to be in Bethlehem rather than merely see it,” Kattan tells #SceneTraveller. “This is a stay designed for those who seek not a checklist, but an experience, not a series of landmarks, but a feeling.”

With only six rooms, Kassa is intimate by design—a far cry from the faceless hotels that dominate the city’s religious tourism industry. Each room is its own quiet sanctuary, a blend of old and new, curated with an almost obsessive attention to detail. The beds, crafted by Palestinian artisans, are heavy with locally woven textiles; the ceramic lamps, made in Hebron, cast warm pools of light; the soaps in the bathrooms are hand-poured, made with Bethlehem-sourced olive oil; the art on the walls a collaboration between Palestinian and Chilean artists, a nod to the bridge between Kassis Sabagh’s two worlds. One striking piece—"The Island of Palestine" by Chilean-Palestinian artist Victor Mahana Nassar—reimagines Palestine as an island, a poetic, devastating metaphor for a nation fragmented by occupation. The painting is a stark visual commentary on the way borders have not only redrawn Palestine but have, in effect, turned it into an archipelago of dismembered spaces, separated by checkpoints and walls. “Our identity as humans is crossed,” explains Sabagh. “What reaches us and represents us can also reach and represent other people from other countries.”

Horses also feature prominently in the art on display, reflecting Sabagh’s own life as a breeder in Chile and a forgotten part of Palestinian culture. “Palestinians had deep bonds with horses until the occupation severed them,” she explains. “Three generations have now lived without them.” Elsewhere, monkey figurines tucked playfully into the décor pay tribute to Abu Shamon Café, which once stood on this very site—a place where the owner’s pet monkey sat perched on his shoulder, delighting customers as they sipped cardamom coffee. Even crowns, scattered throughout Kassa, hold a quiet message: “Each and every one of us deserves to be treated like kings and queens,” Sabagh says, reflecting on a tattoo of a crowned heart that she has on her sleeve. “Because being kings without love is useless.”

The wines served tell a similar story—palimpsests of history in every glass. “The Natufians, those early inhabitants of Jericho, were, after all, the first people to cultivate grapes some 9,500 years ago,” explains Kattan. “It’s in the soil, in the bones of this land.”

But for all its artistry, this place is now silent, standing in eerie stillness. The genocide in Gaza has rendered Bethlehem a ghost town, its streets emptied of the usual procession of visitors. Just last week, Fadi Kattan, co-founder of Kassa, was wandering into the Church of the Nativity and found it vacant, the hushed reverence now replaced by unsettling absence. New Year’s Eve, once a reliably bustling occasion, saw the hotel that stands at the busiest street in town at half capacity. Bethlehem, that has hosted travelers for thousands of years, suddenly finds itself devoid of them.

But even in silence, Kassa persists. They are still open and still sustaining themselves.

Kattan resists the idea that his work, in cooking or in the realm of hospitality, is done primarily with the intention of being an act of defiance or of resistance, though he acknowledges that to the observer, it is. “I want to welcome people. I don’t do what I do with defiance and resilience in mind. I just want to represent my people and celebrate my culture with love first, and then resilience comes.”

- Previous Article WATCH: Asser Yassin on Ramadan Hit Series ‘Qalby W Moftaho’

- Next Article The Saudi Restaurant Londoners are Flocking To

Trending This Week

-

Mar 29, 2025